‘Best breeding season yet’ expected for B.C.’s endangered owls

Wednesday, May 1, 2019

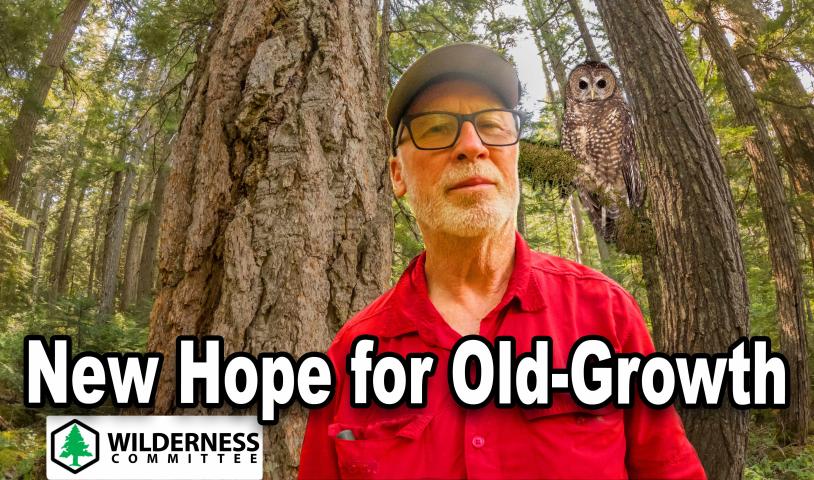

The rare northern spotted owl is being bred at a conservation program near Fort Langley

A new generation of endangered owls is expected to hatch soon in a conservation centre nestled in the hills near Fort Langley.

“We’re looking forward to what seems like our best breeding season yet,” said Jasmine McCulligh, the facility coordinator for the Northern Spotted Owl Breeding Program.

For 10 years, the BC Conservation Foundation has been painstakingly working to bring back the endangered owls from the brink of extinction in this province.

The centre raises and feeds their owls in large netted enclosures, big enough to allow the owls to fly and even to hunt live prey at times.

Now with five breeding pairs, including two that are new this year, McCulligh says things are looking up for the program.

She can’t say exactly how many eggs have hatched this year yet. The program is planning to make a major announcement as early as this weekend.

If things go well, it could mean northern spotted owls being reintroduced to the wild, for the first time since the program began, as early as next year to a few years from now.

The breeders include Jay and Bella, a captive-born pair that recently bonded, and Azalea and Einstein, who were brought to the centre as juveniles.

Although the owls are in captivity, they rarely interact with or even see their keepers, McCulligh said.

“We are very hands-off with them,” she said.

The adults get a check-in every morning, with the keepers scoping them out, to ensure they are dry and have clear eyes, “like a normal healthy owl.”

They get another check in at feeding time, and other than that they are left to their own devices.

Other than that, the main method of watching the owls is through cameras, with four to each enclosure including one directly above each nest.

That becomes important for the breeding pairs around March, when eggs are laid.

The eggs incubate for about 32 days, with the female staying on nest all day and night, with only a brief 20 minute break to defecate.

The male brings food to keep her going during the incubation period.

However, for the spotted owls in the Langley centre, things aren’t what they seem. The owls are brooding over robotic eggs.

To give them the best shot at hatching, staff remove the eggs from the nest and place them in incubators.

The parents receive robotic sensor eggs in return, which measure temperature and humidity in the nests, said McCulligh.

“She’s not too concerned about the difference in the eggs,” McCulligh said.

Staff at the centre watch over the eggs as they hatch, and then hand-feed each chick for about 10 days to give them a “head start” during a period when they’re highly susceptible to bacterial infection.

Then the chicks go back in the nest.

If the parents are surprised by the appearance of 10-day-old chicks, it doesn’t seem to last for long.

“I guess they think, ‘Oh, you did the hard part for me,’” said McCulligh.

Staff have even successfully introduced chicks that weren’t hatched by those parents. A three-week-old abandoned chick found in the wild was once successfully raised by a breeding pair at the centre.

The young owls leave their parents in the fall, removed to their own enclosures just before they would fly away under their own steam in the wild.

The owls are distributed around 21 enclosures spread over 25 acres.

In the wild, McCulligh said a pair of spotted owls would have as much as 30 square kilometres of territory, and there would never be 25 owls all gathered in one place.

But here, the staff largely worry about keeping dominant males far enough apart that they don’t bother one another.

Food for the owls is less than appetizing from a human point of view.

“We breed our own rats and mice on site,” said McCulligh, and they also provide dead chicks at times.

Multiple times a year, they release live rodents into the enclosures, so the owls continue to hunt.

“The hunting instinct is pretty strong in them,” she said.

The long term goal of the program, which is funded by the BC Ministry of Forests and Lands, is to start releasing the owls into the wild.

With 20 adults now, that could happen as soon as next year if things go well with the current crop of hatchlings.

If too many owlets don’t survive, it could be a few more years.

With the big announcement upcoming, the program is also hoping to raise some more money for its operations with its Adopt An Egg program.

“We’re actually a bit short of our goal,” McCulligh said.

People who donate $20 to symbolically adopt an egg get email updates and info about the progress of ‘their’ egg.