Burnaby Mountain Lawsuit Renews Anti-SLAPP Calls

The Tyee

One of Burnaby's most outspoken Kinder Morgan opponents is headed back to court today, demanding the pipeline company pay his legal fees and "special costs" for dragging him through what his lawyers allege is a frivolous legal battle.

The motion by Burnaby Residents Opposing Kinder Morgan Expansion (BROKE) member Alan Dutton is the latest development in an ongoing $5.6-million lawsuit against him and four other BROKE members. Kinder Morgan accused them of assault and trespassing in their anti-Trans Mountain pipeline efforts.

"We say Dutton is being sued by Kinder Morgan because he’s an organizer, and because Kinder Morgan wants to silence him and discourage him from organizing people in opposition to the pipeline," alleged his lawyer, Neil Chantler, in a phone interview. "He’s incurred expensive legal costs defending himself to date, and we say he should be compensated."

Although four of his fellow defendants quietly settled with the company, Dutton refused because he believes the company's lawsuit is a "strategic lawsuit against public participation," otherwise known as a "SLAPP" suit. The term describes a vexatious case never intended to go to trial, but simply to intimidate.

Trans Mountain spokeswoman Ali Hounsell disputed that accusation in an email, and said the injunction was "never intended to prevent or deter people from freely expressing their views."

"It is unfortunate Mr. Dutton has chosen to pursue further legal actions, and we believe his motion to be without merit," she wrote, adding that the firm did truly suffer the damages it listed in its claim against Dutton, including financial losses from protests which impeded their exploratory drilling in Burnaby Mountain Conservation Area, and hostilities towards workers.

Vancouver-based firm Taseko Mines Ltd. has also been recently accused of filing a SLAPP suit. The company is suing several environmental opponents for defamation over statements they made about its proposed New Prosperity mine's tailings waste plan. The claims have not yet been tested in court, but one of the defendants, Wilderness Committee's Joe Foy, alleged the case is a classic example of a SLAPP suit.

The accusation that powerful financial interests can abuse the court process to intimidate ordinary citizens is not a new one. In the 1990s, a concerted push to outlaw SLAPP suits led the B.C. New Democrats to pass a Protection of Public Participation Act in 2001, only to see BC Liberal attorney general Geoff Plant repeal the law months later after his party's landslide victory.

Now, the original proponents of anti-SLAPP legislation, along with the BC NDP, have renewed their call for more rigorous anti-SLAPP laws in B.C. They want new laws that enable judges to more quickly dismiss corporate lawsuits aimed solely at shutting down the voices of oppositional citizens.

'A comprehensive problem'

Two decades ago, lawyer Greg McDade helped lead the anti-SLAPP campaign in B.C. and helped draft proposed legislation that gained traction with the provincial government.

It was during his tenure as executive director of the Sierra Legal Defence Fund (since renamed Ecojustice) when he first heard the "SLAPP" moniker from the U.S. He thought it fit some of the logging cases he was working on.

"It became apparent that there was a comprehensive problem here, where deep-pocketed companies or rich developers can use the courts as an abusive mechanism to try to shut down people," Dade said.

Today, the North Vancouver-based lawyer is a partner at Ratcliff and Co. and represents the City of Burnaby in its ongoing legal challenges to the National Energy Board and Kinder Morgan.

SLAPP suits "work very well, unfortunately," he said. When outspoken corporate critics get sued, "they're worried about their house, their spouses are telling them, 'Why are you putting our kids' future at risk?' Even if their lawyers are telling them there's zero chance of success, suddenly you find all sorts of very responsible people dropping out of the fight."

According to McDade and other SLAPP critics, even when judges throw such cases out as frivolous, it doesn't matter to the plaintiffs. Because courts are concerned with protecting the right to sue, it's hard to get such cases tossed early.

"They don't care if it's thrown out," he said. "They just want to make you spend a whole bunch of money, and keep you scared."

Another lawyer who worked with McDade to draft proposed legislation in the 1990s was Chris Tollefson, who today heads up the University of Victoria's Environmental Law Centre. Even as a lawyer, Tollefson said he too has felt the chill effect of SLAPPs.

"And I know how to defend myself. Think about an ordinary citizen's life: to pay the legal fees, and on top of that the stress, can be just crippling," he said.

"It's really essential that the legal system identify this phenomenon and develop a way to respond to it effectively. The existing mechanisms we have in our legal systems are not adequate to do that."

SLAPP laws too risky?

When the '90s-era NDP began to discuss anti-SLAPP legislation, its most outspoken critic was then-justice critic Plant, who would go on to kill it as attorney general.

At the time, Plant argued in the legislature that B.C.'s legal system already has adequate mechanisms for judges to toss frivolous lawsuits, and that legislating the matter would unfairly restrict people's access to justice.

In an interview last week at his Gall Legge Grant & Munroe offices, Plant maintained his concern that governments shouldn't restrict access to courts, regardless of the plaintiffs' intent.

"It's risky for us to decide that you're allowed to proceed with a lawsuit only if it is well-intentioned," he said. "We don't ask people why they've sued, any more than we ask people why they voted."

Plant said that beyond a handful of B.C. cases cited by Tollefson, he sees little evidence that SLAPPs are as widespread or systemic enough to warrant legislative intervention. He did acknowledge, however, that fighting lawsuits is prohibitively costly for most.

"You can't discount the risk that there are some people who will use litigation for any number of strategic purposes. That has always been the case," he said. "But I don't think that the absence of SLAPP legislation has paralyzed free speech in British Columbia. I don't see a change of circumstances that would cause me, if I were a cabinet minister, to want to re-open the discussion."

Tollefson agrees that litigants should be given "broad latitude" to launch lawsuits. But the onus to prove a case is not frivolous should be shifted to the suers, not the sued, he argues -- and if a judge rules in the defendants' favour, damages beyond simply legal costs should be awarded.

"What we've seen is a surge in litigiousness around resource development issues that resort to the courts," he said. "SLAPP suits are not going away; if anything, they're on the rise. The time has come for that discussion to start over again."

Judges 'no friend of privilege': Plant

The last time the provincial Opposition took on SLAPPs was 2008, when the NDP's attorney general critic Leonard Krog tabled an Anti SLAPP Act. The attempt failed, but the party remains committed to some sort of legislative remedy.

"Anti-SLAPP legislation would provide some guarantee that access is still there for people who don't have deep pockets," Krog said in a phone interview.

Attorney General Suzanne Anton was unavailable for an interview, but a spokesman said in an email that current court rules are adequate to offering redress for frivolous cases.

The province, along with most Canadian jurisdictions, do not provide for what is sometimes described as 'anti-SLAPP' legislation, the email said. "The challenge with such legislation, is determining the basis for dismissing a civil claim prior to a hearing on its merits."

Tollefson pointed to Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne's backing such efforts there, after a provincial Blue Ribbon panel favourably reviewed B.C.'s 2001 law and recommended pursuing something similar.

For former attorney general Plant, a better approach to the perceived problem of SLAPP suits is to "vigorously" fight them in the courts. Judges are "no friend of privilege" and harbour little patience for cases without merit, he said.

"There's nothing to prevent someone who is articulate enough to express their opposition to some issue of public interest to maintain that opposition in a courtroom," he said.

That may be cold comfort for Dutton as he prepares for today's court appearance. As the only Kinder Morgan defendant left on the docket, he insists walking away isn't an option because he believes free speech is at risk.

"This case is one that affects everybody's rights," he said. "If multinational corporations can get away with suppressing Charter rights for me, they can get away with it for you and everybody else."

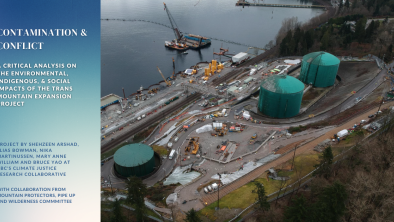

Photo: Police on Burnaby Mountain. Kristin Henry.