Canada Seeks Alternatives to Transport Oil Reserves

New York Times

As the United States continues to play political Ping-Pong with the fate of the Keystone XL pipeline, Canadian officials and companies are desperately seeking alternatives to get the country's nearly 200 billion barrels in oil reserves — almost equal to that of Saudi Arabia — to market from landlocked Alberta.

Oil companies complain that they are losing revenues from pipeline bottlenecks. So Canada is plunging ahead with plans to build more pipelines of its own.

To hasten development of new export routes, the Conservative government is streamlining permit processes by accelerating scheduled hearings and limiting public comment. The government has also threatened to revoke the charitable status of environmental groups that are challenging the projects. And Public Safety Canada, the equivalent of the United States Department of Homeland Security, has classified environmentalists as a potential source of domestic terrorism, adding them to a list that includes white supremacists.

After President Obama refused to grant a permit for Keystone XL in January, Stephen Harper, Canada’s prime minister, indicated that he would never again be “held hostage” to United States politics, saying that some Americans saw his country as “one giant national park.” He said Canada would redirect oil that had been destined for Gulf Coast refineries to other countries, particularly China.

While Joe Oliver, Canada’s minister of natural resources, said in an interview that the United States would remain Canada’s “most important customer,” billions of barrels of oil that would have been refined and used in the United States are now poised to head elsewhere. Expansion of Canada’s fast-growing oil-sands industry will be restricted by the lack of pipeline capacity before the decade’s end, he said, which “adds to the urgency of building them so that the resources will not be stranded.”

Three new pipeline network proposals — two that call for heading west and the other east — have been put forward. In May, Enbridge, a transporter of Canadian oil exports, announced a $3 billion plan called Eastern Access. It is seeking permission to build a new “Northern Gateway Pipelines” network, to bring 525,000 barrels a day to Canada’s Pacific Coast. Kinder Morgan, a Texas-based energy company, said it will nearly double the capacity of an existing pipeline network along a different route.

Together, the new westward pipelines would carry more oil than Keystone XL would. But even with aggressive government backing, creating new pipelines may prove as difficult in Canada as it has been in the United States, though for different reasons.

Indigenous groups must be consulted if new pipelines cross their land. To gain coastal access, pipeline companies must also navigate the politics of some of the most environmentally conscious Canadian provinces, British Columbia and Quebec, where public opinion tends to be against both pipelines and further fossil fuel development.

Vancouver’s City Council recently passed a motion requiring that pipeline companies take on 100 percent liability for the economic and environmental costs of a worst-case spill. Even though the federal government gives permissions for pipelines, such local maneuvering and lawsuits can cause severe delays.

“It’s poetic justice that Vancouver, the birthplace of Greenpeace, stands between the last big oil deposit on Earth and the expanding markets in Asia,” said Ben West of the Wilderness Committee, a consortium of environmental groups. “I’d anticipate it won’t get built for years.”

Mr. Obama said no to Keystone XL over issues of routing and insufficient environmental analysis, after a showdown with Congressional Republicans. No further action is expected before next year, although the pipeline builder, TransCanada, has reapplied for a permit.

But as pipeline companies cast about, the United States may again be drawn into the fray over routes in other parts of the country. The most likely eastern Canadian pipeline route would reverse existing pipelines through Ontario and Quebec, and then cross the border into Vermont, heading to a tanker port in Portland, Me. Such a project was proposed in 2008 but dropped during the recession.

A State Department spokesman said it had not fielded inquiries to revive the idea, but residents of the United States’s Northeast are organizing against it. Without a reliable way out, Canadian oil often trades for $30 a barrel less than other crudes, said Todd Nogier, an Enbridge spokesman. The company estimates its proposed new westbound pipeline will increase Canada’s gross domestic product by $270 billion over 30 years. Chinese companies have already invested in Canadian oil sands.

Environmentalists are not nearly as enthusiastic. One reason is that Canadian oil is extracted in a process that creates relatively high emissions of carbon dioxide. Also, oil from oil sands is exported as bitumen, a gritty paste that must be thinned with chemicals for transport.

The United States Pipeline Safety and Hazardous Materials Administration is studying whether diluted bitumen is more corrosive and prone to dangerous spills than conventional crude, thus requiring special regulation. The report is due next year. A 2010 spill of diluted bitumen from an Enbridge pipeline in Battle Creek, Mich., has cost over $720 million, and parts of the Kalamazoo River remain closed.

In Canada, environmental groups and opposition politicians say Mr. Harper’s government is trampling on civil liberties and due process in its rush to get bitumen to market. Public hearings on proposed pipelines were expedited from the fall to the spring, leaving groups little time to organize and mount challenges to inadequate environmental analysis of the impacts, said Gillian McEachern of Environmental Defense, a Canadian environment group.

Ms. McEachern said that the application process for public comment was made so complicated that many with opposing views were shut out.

Last month here in London, a coalition that included environmentalists and members of aboriginal tribes disrupted what was to have been an obscure public hearing. Enbridge’s Eastern Access expansion plan involves moving bitumen from Alberta east to Montreal by reversing the directional flow in older pipelines that now carry refined oil westward to Ontario. The hearing was solely about allowing a change of direction for a 100-mile pipeline segment.

“We sent a letter asking to speak and didn’t even get a reply,” said Wes Elliot, of the Six Nations indigenous group, one of several dozen ejected by the police for speaking without permission. The hearing was then closed to the public. On the curb outside, he said he worried about spills.

Under Canadian law, aboriginal groups must be consulted about pipeline projects that cross their lands. Enbridge has offered many tribes a 10 percent stake in its westward pipeline project; Graham White, an Enbridge spokesman, said about half have accepted.

Others in attendance said proposed bitumen pipelines would traverse vital agricultural aquifers — concerns that tripped up Keystone XL in the United States.

“They say they’re just tinkering with existing pipeline,” said Steven Guilbeault, co-founder of Equiterre, a Canadian environmental group. “We think they’re doing it bit by bit so they won’t attract attention like Keystone.”

Mr. White said there was currently no plan for a pipeline extending into the United States, but would not rule it out in the case of market demand.

Groups in Vermont and Maine are girding for a fight, concerned most about spills in Maine’s Casco Bay, a center of fishing and tourism. Glen Brand, head of the Sierra Club’s Maine chapter, said that a meeting on the issue in Bangor this spring attracted over 100 people. On both coasts of North America, residents object to a predicted manyfold increase in tanker traffic in harbors where people relocate to enjoy the pristine beauty. Simon Donner, a scientist at the University of British Columbia, sees the pipeline as symptomatic of the weakness of Canada’s climate policy, and said he thinks the Canadian government is underestimating the opposition. “People won’t roll over on this issue,” he said.

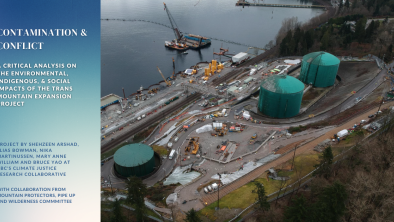

Photo: A tank farm on Burnaby Mountain, just east of Vancouver, provides storage for oil transported from Alberta. New pipeline projects would require double the capacity of the existing tanks.