Canada unprepared for oil spill in Strait of Juan de Fuca

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Canada is not ready to respond to an oil tanker spill — large or small — in the Strait of Juan de Fuca or inland waters shared by Washington’s San Juan Islands and British Columbia’s Gulf Islands, according to a panel appointed by pro-oil Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

The Canadian waters “with the highest probability of a large spill occurring” are at the southern tip of Vancouver Island as well as the Cabot Strait and the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Eastern Canada, the panel concluded. And places with the “highest potential” for smaller spills include the southern coast of British Columbia, including Vancouver Island.

The panel’s report comes as Harper’s government is eager to give a green light to two huge pipeline projects that would see up to 650 tankers plying the British Columbia coastline.

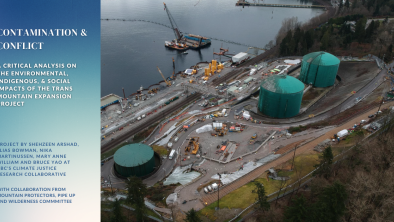

Both would carry oil from the huge tar sands (officially “oil sands”) project in Northern Alberta to the West Coast of Canada for export abroad. One proposal, the $5.4 billion Kinder-Morgan proposal, would terminate in Burnaby, just east of Vancouver.

The Canadian government panel made 45 recommendations and cited high-risk areas on both coasts, notably the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the south coast of Vancouver Island.

“For example, in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Canada should be prepared for a spill of crude oil due to the volumes being moved and the environmental and socio-economic sensitivities present,” said the panel, chaired by Gordon Houston, former president of the Port of Vancouver.

If a tanker out of Burnaby were to have an accident in Haro Strait, which forms the U.S.-Canada border, the newly created San Juan Islands National Monument would be directly in its path.

A pair of legendary beauty spots in the San Juan Islands — Turn Point on Stuart Island, and Patos Island — front on the sailing route taken by tankers. So does the San Juan Island National Historical Park.

The Harper government unveiled the panel’s report as part of its campaign to persuade British Columbia to accept the Kinder Morgan pipeline. It is particularly anxious to move public opinion to favor the larger $6.5 million Northern Gateway pipeline, which would terminate at Kitimat in northern British Columbia. Kitimat is at the head of a long, narrow fjord, along a coast notorious for stormy waters.

“We will act on the advice from the panel and will work to create a world class tanker safety system here in Canada,” said Transport Minister Lisa Raitt.

The promise begs credulity. The Canadian government recently closed a Canadian Coast Guard station in Vancouver’s Kitsilano. It also shut down the Vancouver Marine Traffic Control Center.

“Under this government, safety has gone from inadequate to worse,” said Bob Peart, a former deputy minister in the British Columbia government and executive director of the Sierra Club of B.C.

“These are international waters,” Peart argued. “They are critical habitat for orcas . . . We sit in our Gulf Islands and look across at the United States, where tanker standards are different — and much better. Americans should take this very seriously.”

The federal panel argued that Canada’s spill response is “fairly sound” and that it was working to clear up “misconceptions” about response to potential accidents. But its findings flagged major issues, including:

– Canada is “not adequately prepared to move quickly on spills,” said the panel, and is overly reliant on “mechanical” spill recovery gear such as skimmers. Spill response vessels pick up, transport, store and dispose of oil.

“These techniques can recover, even in ‘optimal’ conditions like calm waters and quick access to the spill, between 5 and 15 percent of spilled oil,” said Houston’s panel.

– Liability: Canada has a $161 million limit on industry-funded compensation for a each oil spill. The figure is a fraction of the billions of dollars that Exxon/Mobil paid out as a result of the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill, which dumped 11.9 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

“Canadian taxpayers should not have any liability for spills in Canadian waters,” said the report, which argued for unlimited liability.

– Readiness: The Canadian government conducted its last preview of oil spill preparedness in the 1990s after the Exxon Valdez spill. Since then, vessel traffic along both coasts has increased by 43 percent.

The Houston panel tried to soft-pedal the readiness issue. “Generally, we found that the fundamental principles of the regime have stood the test of time,” said its report, “but that there are a number of areas that could be improved to enhance Canada’s preparedness and response to ship source oil spills.”

– Coordination: Three government departments — the Canadian Coast Guard, Transport Canada and Environment Canada — share responsibility for tanker safety and spills. The agencies are operating as “silos” without adequate coordination, argued the report.

The absence of coordination is vitally important, due to Canada’s past performance when confronted with a winter spill in Northwest waters.

The barge Nestucca broke up in 1988 off Grays Harbor, spilling oil into U.S. waters. The oil was carried north more than 100 miles, where it fouled beaches in Canada’s Pacific Rim National Park. The Canadian Coast Guard was totally unprepared — with no response plan and little response — for foamy oil coming ashore on Long Beach and in pristine Florencia Bay.

While Canada’s provinces have vast powers on land, the federal government has prime jurisdiction over marine waters.

“The current state of affairs is not one where we have the capacity to respond to such an event (major spill),” B.C. Environment Minister Mary Polak told reporters Tuesday.

Polak was, however, full of praise for what she described as a “dramatic change” in the attitude of Canada’s federal government. Ottawa is “serious about the safety of our coast,” she added.

The Harper government, and oil companies, have launched a concerted propaganda campaign to overcome B.C.’s opposition particularly to the Northern Gateway Terminal. The pipeline’s builder is airing TV ads on how safe tankers are and has bought newspaper ads showing a whale’s tail flapping out of the water.

The Canadian government has worked “almost as a public relations firm for the oil companies,” said Eoin Madden of the Wilderness Committee, an environmental group fighting the pipelines. “We absolutely expect the federal government to approve this (Northern Gateway) pipeline.”

The Harper government has cut funding from agencies like the Coast Guard “that keep us safe” while “the only thing they have upgraded is the message they are trying to sell the public.”

The government of British Columbia Premier Christy Clark appears ready to go along with one or both pipelines but has put five conditions on the Northern Gateway project. “It is certainly the right of the federal government to make decisions within their jurisdiction,” Polak said Tuesday.

“It is very much the provincial government hiding behind the federal government,” said Madden of the Wilderness Committee.

The great oil spills of the past 45 years, from Santa Barbara Channel to Scotland, from the coast of Brittany in France to Alaska’s Prince William Sound, have featured heart-tugging photos of oil-coated birds, otters and other marine life.

The Houston panel found Canada “particularly lacking” in capacity to rescue and rehabilitate wildlife caught in a major spill, or whatever oiled wastes are collected.