First Nations band wants to develop 'tribal park'

Edmonton Journal

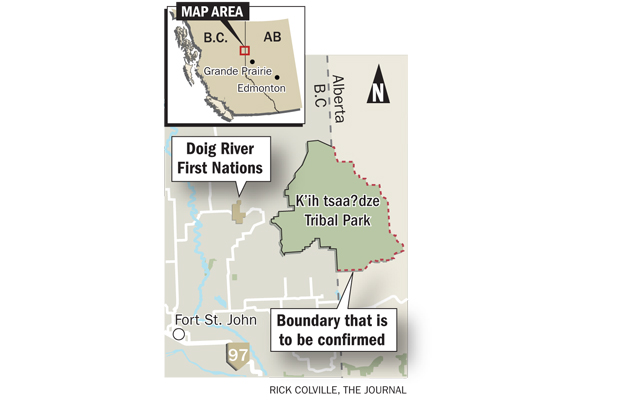

A northern First Nations band has announced plans to develop Alberta's first "tribal park," a protected area of about 90,000 hectares straddling the province's border with British Columbia.

"This area has been in our traditional territory (for) camping and hunting. It's a spiritual area for our people," said Doig River Nation Chief Norman Davis, adding the land - which takes in Sweeney and McLean creeks northwest of Grande Prairie and southwest of Chinchaga Wildland Provincial Park - has been his people's place "for generations, since even before the border was put in."

At this time, Ottawa is calling the tribal park plan a "unilateral declaration by the Doig River First Nation related to lands under provincial jurisdiction within Alberta and British Columbia."

The federal government is not in negotiations with the Doig River band in relation to the tribal park, Geneviève Guibert, a spokeswoman for Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, said.

Alberta government spokespeople said the province is not involved in such discussions at this time.

Davis said the goal of the park is to "try to protect what we have in this area," including the forests K'ih Tsaa? dze - the proposed name of the tribal park - means "old growth area."

While land west of the border - about 50 kilometres northeast of Fort St. John - has been surveyed by B.C.-based consulting company Silva Ecosystems, field assessments of the Alberta side of the proposed park have not yet been undertaken. It is unclear what effect the park would have on oil and gas work in the area. "In the past there's some activities that went on there, like oil and gas," Davis said. "The industry has been - respectful, staying out of this area, to our nation."

While a first for Alberta, the K'ih Tsaa? dze tribal park would not be Canada's first. Since the 1980s, First Nations groups in British Columbia have declared at least three areas as tribal parks - the South Moresby area in the southern Queen Charlotte Islands, Meares Island at Clayoquot Sound, and, more recently, Haa'uukmin, also at Clayoquot Sound near Tofino.

"It is a way, I believe, for First Nations to be proactive in land-use planning on their territory," said Joe Foy, national campaign director to the Vancouver-based Wilderness Committee.

The tribal parks along B.C.'s West Coast islands also started with unilateral declarations designed to prevent forestry companies from moving into their territories. The Meares Island tribal park claim was resolved in part through a court injunction in the mid-1980s. Foy called the unilateral declarations the opening move in long-term efforts of First Nations groups to decide for themselves how their land will be used.

"It brings together a number of things (including) a very interesting question, a very important question to all Canadians, about what is Canada - when we exist on top of pre-existing nations," Foy said.

"We used to rough ride along the Peace River. As the early settlers (came) in, we were pushed further back," said band councillor Gerry Attachie, 63, a former chief of the Doig River Nation.

"As the early settlers, farmers, (came) in, some of the places we used to go (were) fenced off (for) farms. So we can't go there anymore," Attachie said.

"In the past you could go anywhere. We've been here forever, even before the Alberta and British Columbia boundary."