Manitoba parks defence

- Industrial activity parks

- Goals for more parks and protected areas

- Indigenous protected areas in Manitoba

- The outdoor recreation community and parks

- Nature and our health

- Parks protecting species

Industrial activity in parks

A major threat to Manitoba provincial parks is mineral exploration, and in Duck Mountain, there is still clearcut logging. The Wilderness Committee continues to call for an end to industrial activity in provincial parks so that we don’t have to worry about parklands being destroyed.

Way back in 1961 when our provincial park designation was established, it was thought that industrial development and protection of nature could co-exist. Scientific studies and traditional ecological knowledge proved long ago that isn’t the case. Industrial activity damages the nature that parks are meant to preserve, but Manitoba is a laggard in park protection.

Park logging

After nearly a decade of the Wilderness Committee generating public awareness about clearcut logging in Manitoba provincial parks, the government announced in 2008 they were ending logging in 12 of 13 parks. In just two years we helped deliver 23,000 letters to the Manitoba government, demanding an end to park logging. Now, Duck Mountain Provincial Park is the only park in Manitoba being actively logged and one of only two in Canada.

Clearcutting for Louisiana-Pacific’s mill in Swan River continues to have a devastating impact in Duck Mountain Provincial Park. The Environment Act licence to log “the Ducks” (as the park is known), was set to expire on Dec. 31 of last year, but Premier Brian Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government quietly extended the licence for another two years.

Park mining

In 2011, the Wilderness Committee broke the story about the destruction caused by mineral exploration in Nopiming Provincial Park. After a subsequent education report released in 2012 entitled ‘Ban Park Mining,’ the Manitoba government agreed to halt mineral exploration in parks. Unfortunately, this agreement was not enshrined in legislation. When Premier Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government came to power he reversed this directive. And in 2018 we uncovered further destruction in Nopiming Provincial Park that is ongoing.

Despite independent polling showing, 70 per cent of Manitobans want industrial activity to be phased out of parks, the Manitoba government continues to allow mining claims and park destruction.

Nopiming, Whiteshell, and Grass River Provincial Parks each have more than half the park unprotected from park mining activity.

Goals for more parks and protected areas

Protecting nature and wilderness from disturbance is not just a feel-good measure that ensures we have places to visit. Protected areas are critical for human society because they are our life support system.

In the 1980s the world was starting to recognize intact nature needed to be preserved for the wellbeing of the planet. Protecting 12 per cent of lands on Earth by 2000 was proposed and most jurisdictions in the world adopted this goal. Manitoba signed on to this agreement in 1992 when not even 1 per cent of the lands were protected, the least protection of any province.

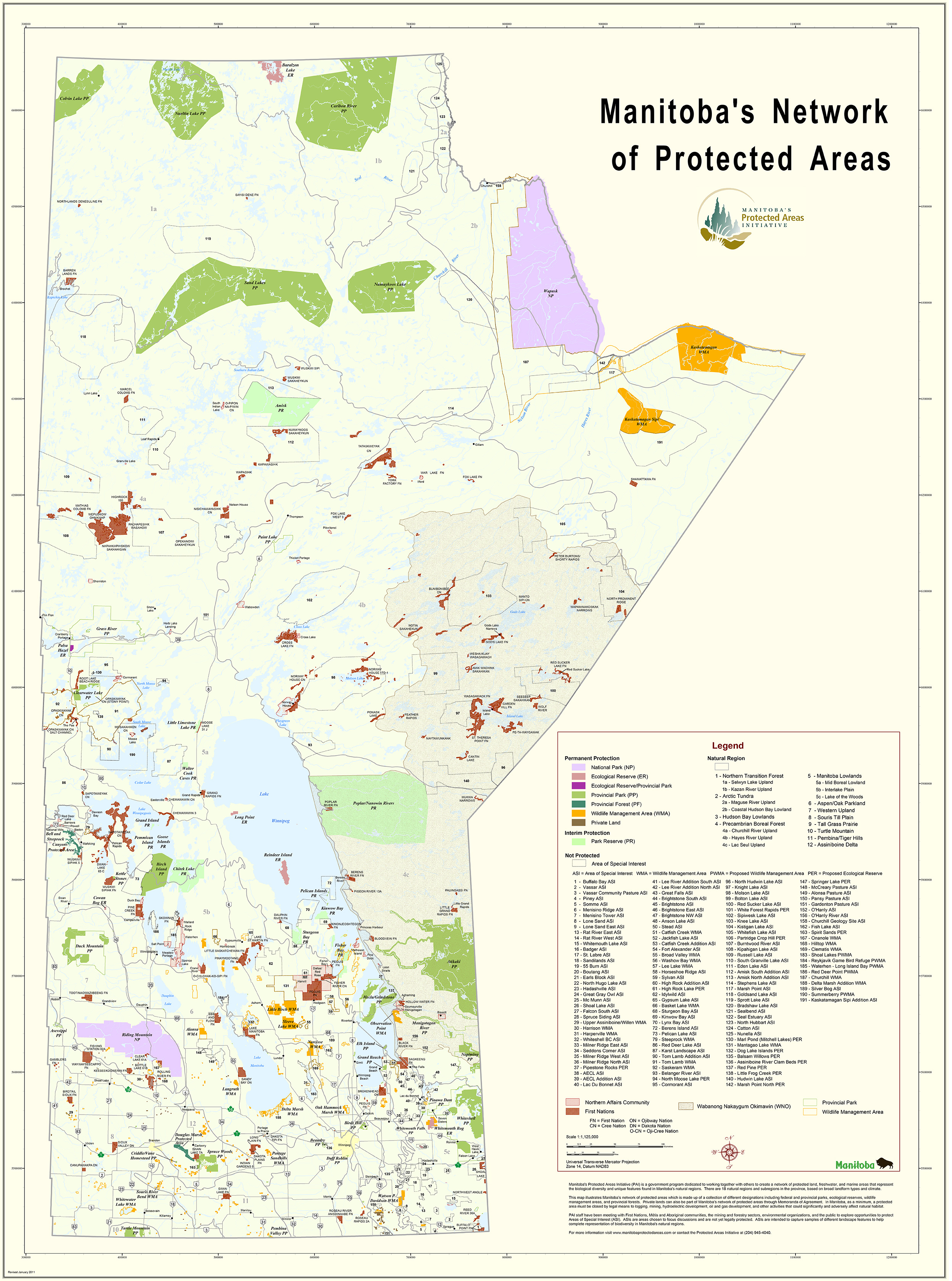

Manitoba established a Protected Areas Initiative (PAI) to move forward on preserving nature in the province. By 2000, 8.6 per cent of the province was protected from development according to standards set by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). PAI worked on hundreds of different areas nominated for protection and published maps and progress reports. The pace of protection was not fast enough to prevent biodiversity decline, but it was progress.

Premier Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government quietly disappeared the PAI in 2019, ending decades of critical work for our province. There’s no science behind ending this initiative, only stale ideology that’s going to harm Manitoba environmentally, economically — and emotionally.

In 2020 Manitoba is now at 11.1 per cent lands protected, still below the old goal and 20 years late. In 2010 the world again set a target of 17 per cent of lands protected by 2020. While Canada has signed on to this goal, Premier Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government refused to. More recently scientists and advocates of the UN Convention on Biodiversity have stated we need to protect 30 per cent of the planet by 2030.

Manitoba needs a protected area goal. We’re not immune to the biodiversity crisis. Rather, we can be global leaders in protection because we have intact nature. But the toxic and persistent notion that short term profit is more important than our life support system is holding us back.

The Wilderness Committee is calling for a target and timeline for protected areas in Manitoba, and for the government to enshrine these targets and timelines in law with the consent of Indigenous communities.

Indigenous protected areas in Manitoba

Indigenous protected areas are the future of conservation work, both in Manitoba and around the globe. Where once parks were overlaid upon Indigenous traditional territory without proper consultation or consent, we must now ensure Indigenous communities are supported as guardians of nature in their territories.

The Wilderness Committee published an educational report, No Conservation without Justice, in September 2020, calling for those in the environmental movement to centre justice for Indigenous peoples in our work, because all the land we’re on is Indigenous land.

We know the creation of parks in Manitoba and Canada hasn’t always been done right, and have sometimes contributed to the further dispossession of Indigenous peoples whose lands and waters have been protected. Any new parks here must be established with the leadership of Indigenous peoples.

In 2011, Fisher Bay Provincial Park was protected at the wishes of Fisher River Cree Nation, to preserve their territory and also offer economic opportunities through tourism. Fisher River Cree Nation continues to ask for expanded boundaries for Fisher Bay Provincial Park, which the Manitoba government must agree to. In 2006, we published Ochiwasahow the Fisher Bay area about the move to establish this park according to the wishes of Fisher River Cree Nation.

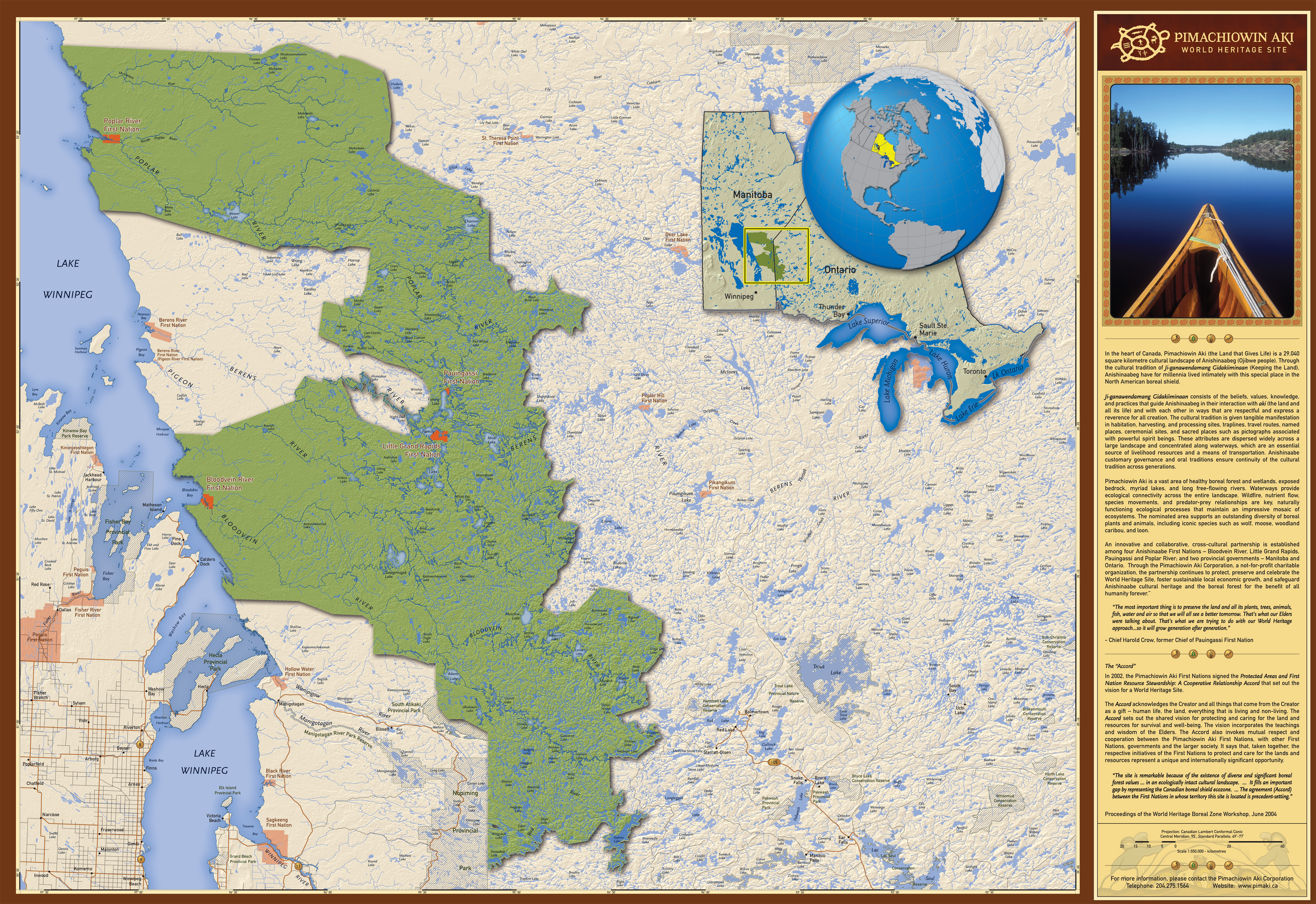

Pimachowin Aki, the Land that Gives Life, is an incredible success story that was protected in 2011. Four communities on the east side of Lake Winnipeg — in the largest forest left intact on the planet — joined together and protected at least half of each of their territories under special protected areas legislation. They also received designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for both cultural and natural reasons. Years of work and thousands of letters collected by the Wilderness Committee assisted in the designation of Pimachowin Aki.

In 2014, Skownan First Nation had part of their traditional territories become the first provincial park in Manitoba protected under an Indigenous Traditional Use classification as Chitek Lake Anishinaabe Provincial Park. Legislation that empowers self-determination and enshrines traditional use in protected areas is what the Wilderness Committee wishes to see.

The outdoor recreation community and parks

Provincial parks are the place where we do our outdoor adventures. Biking the Blue Highway trail in Whiteshell, skiing the Spruce Woods trails or canoeing the Bird River in Nopiming — parks are where our outdoor recreation happens. But to continue to enjoy ourselves out in our parks, we as the outdoor recreation community need to advocate for parks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has kept people in Manitoba, and also pushed people to spend time outdoors. The sheer number of people out on the trails and routes is overloading a neglected park system. In Nopiming the tiny Rabbit River canoe route parking lot was overflowing with 47 cars on the May long weekend, and it was reported that 202 people hiked through the Mantario trail in the Whiteshell on the September long weekend. Our recreation destinations are being heavily used.

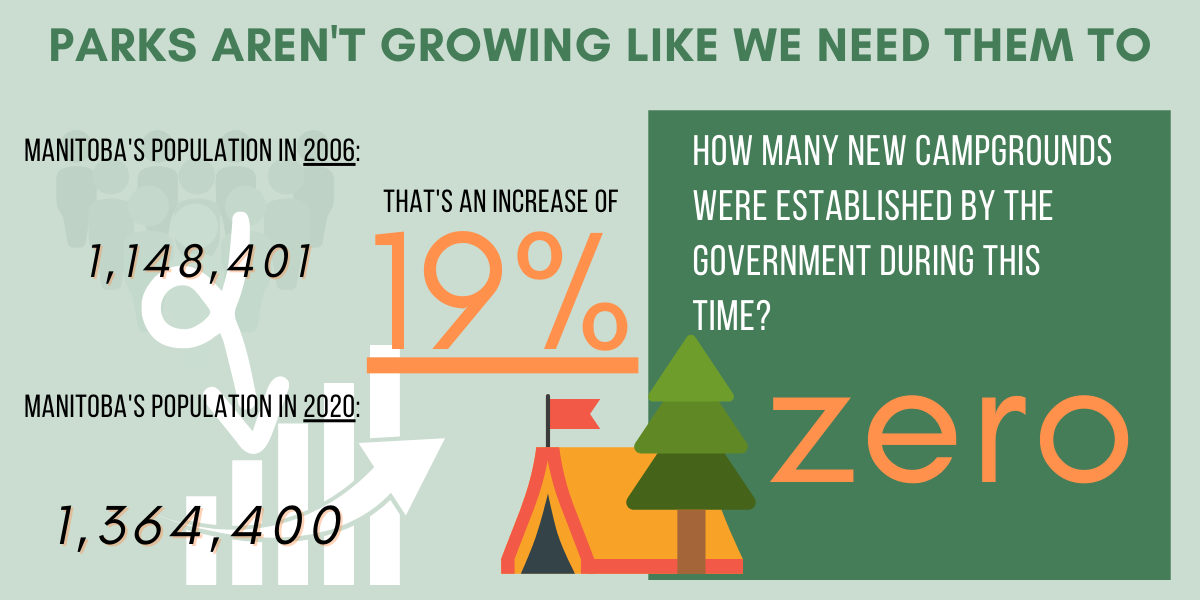

Even outside of a pandemic, the numbers show our parks are not growing as we need them to.

The Manitoba population in the 2006 census was 1,148,401. In 2020 Statistics Canada estimates it at 1,364,400, an increase of 19 per cent. And the number of new park campgrounds during that time? Zero.

Funding for the conservation department in 2006 was $114 million. In 2020 it was $145 million. That’s a difference of 27 per cent, however cumulative inflation during that time in Canada was 25 per cent. Our parks funding is barely keeping pace with inflation, never mind the population.

The need from the government is three-fold. We need more parks and protected areas with campgrounds, we need an increase in human-powered trails and backcountry destinations and we need a larger parks budget.

Nature and our health

Parks and protected areas aren’t just for the health of the planet. Time in nature is good for human health and will lower our rising public healthcare costs.

[Excerpt from Keep it Wild, 2016:]

In today’s society, not nearly as many people are spending time outside; visits in nature are decreasing. Yet studies are increasingly showing that there is science behind feeling better – and healthier — in nature. A study in Finland showed that just 20 minutes of walking through trees, as opposed to walking on a city street, lowered stress levels. Study after study is finding that stress relief is a huge benefit we draw from nature. At the Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, California, one doctor has begun writing prescriptions for outpatient families to go visit parks as part of their recovery.

Taxpayers spend billions of dollars a year on health care. Yet the prevalence of nature, and our exposure to it, could contribute to lowering those costs. While setting aside large areas of wilderness is the best way to protect biodiversity, local “pocket wilderness” areas that are close at hand and accessible to all should also be a priority as we protect more of Manitoba.

Parks protecting species

One of the international biodiversity goals of the last decade was to ‘improve and sustain species that were threatened’ but unfortunately Manitoba can point to almost no work being completed during this period. The health of plant and animal species is what creates the interconnected web of life that makes human society possible. The fundamental path to care for species is by protecting their homes. Habitat preservation in parks and protected areas is essential for species.

Provincial parks and protected areas offer the best opportunity to care for habitat in a way that causes species abundance. Yet most often we are not making protected areas decisions for species, and not managing parks in the best interest of species. It’s not just threatened species needing care. Moose populations plummeted across the province a decade ago and little improvement has been seen.

A 2011 draft action plan for boreal woodland caribou in the Owl - Flintstone Lake range — perhaps the only action plan ever produced for species in the province — recommended new protected areas in Nopiming Provincial Park and adjacent to the park encompassing critical habitat for these animals. Yet by 2020 we still haven’t finalized the plan nor moved to protect their home in Nopiming, which is still being threatened by mining operations.

In 2013, a section of Grass River Park identified as a migration route for boreal caribou for over 20 years was suddenly cleared for a new mine. The government’s line at the time was that the caribou had moved, even though the islands on Reed Lake they were migrating to calve had obviously not moved.

From polar bear den sites to creeks protecting fish habitat to nesting forest for Canada warblers, our parks and protected areas need to be expanded and appropriately managed to support an abundance of species.