Spiritual Leaders Vow to Defend Mother Earth from Oil Sands and Pipelines With Spiritual Declaration

Indian Country Today

Indigenous spiritual leaders from across the continent have launched a declaration to protect Mother Earth from the impacts of development in Canada's oil sands mega-project.The statement, signed by more than 20 spiritual chiefs at a Sundance this summer in South Dakota, includes members of the Lakota, Navajo, Apache, Mohawk, Dine, Aztec and Ojibwe nations, spanning much of Turtle Island.

“It is our responsibility to protect and care for these elements in accordance with our own sacred Laws and Traditions, and in doing so, maintain our spiritual relationship to the land, water, plants, animals, our ancestors, all of our relations and future generations,” reads the declaration, obtained by Indian Country Today Media Network. “We therefore will defend our land and exercise our own Laws and Traditions from all directions to oppose in all Tar Sands pipeline and tanker projects, and the Tar Sands development itself, all of which threaten the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being of all of our relations.”

The statement was envisioned by Sundance Chief Rueben George, of Tsleil Waututh nation in North Vancouver, British Columbia, and signed at a ceremony hosted by Sicangu Lakota spiritual leader Leonard Crow Dog.

According to George, several dozen Sundancers, spanning from Alaska down even to Peru in South America, backed the declaration. The Keystone XL pipeline has seen protests and civil disobedience arrests from opponents hoping President Barack Obama will reject it. The project has generated significant opposition from Native American nations along its route worried about oil spills and pollution.

“The Keystone pipeline goes right through their territory,” George told Indian Country Today Media Network. “It was beautiful to have so many chiefs come together, because [be it] in Peru or up in Alaska or here in Vancouver, we're dealing with the same problems: fossil fuel problems. We also spoke of alternatives, too. Our ceremonies and beliefs come from the elements Earth: from fire, earth, water and sky. That's why we believe our lands and waters are sacred.”

For Crow Dog—the spiritual leader of the American Indian Movement who presided over the late Native American activist Russell Means’s memorial service—it is important that all tribes come together to defend the land from corporations.

“As First Nations people, we kept this land as very holy,” Crow Dog told ICTMN. “If we're going to take anything from the Earth, we offer tobacco. That's why we are still the caretakers of this land, and [why] the land still takes care of us. There are lots of tribes, especially people who live in the bush, that are concerned; we're all concerned. The land is holy to us. But the biggest corporations do not think like that. They want to take all the oil and the gas. But as First Nations people of Turtle Island, we believe this land is still under our custody.”

The oil sands are one of the largest industrial projects on Earth. Located in northern Alberta, Canada, the region is where dozens of the world's biggest energy companies mine the earth to extract bitumen crude that lies under 34.6 million acres—the third-largest proven crude oil reserve in the world next to Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, according to the Alberta government. With increasing demand for new oil sources, Canada's government is ramping up its support for pipelines to export the bitumen to markets in Asia, the U.S. and beyond.

The project's proponents argue that Canada is a more ethical supply of fossil fuels compared to other sources in the Middle East and South America. And they say the sands' environmental impacts, including sprawling open pit mines and tailings ponds, can one day be remediated. But environmentalists warn that on top of the risks of pipeline spills, such as Enbridge's Kalamazoo River, Michigan disaster in 2010, burning the oil sands fuel itself will contribute irreversibly to climate change.

In the wake of Superstorm Sandy—which killed dozens of people in the U.S. and at least 54 in the Caribbean—the warning signs, they say, are ominous.

“Hurricane Sandy seemed to me to be like the earth crying out for us to stop our shortsighted and destructive ways,” said Ben West, an environmental campaigner in Vancouver, B.C. who helped write the declaration. “The tar sands in Alberta are one of the biggest sources of dirty and unsustainable energy left on the planet. Pulling more long dead fossil from the earth to burn and pollute the sky and the atmosphere must come to an end. It is critical that we stop these pipeline projects that would take us further down the road of causing more and more extreme weather events.”

For West, witnessing the chiefs' signing ceremony underlined the importance of the document as more than a political position statement. Prayer itself, he said, is needed, as well as protest.

“These are the teachings that embody the values that should be driving our decisions,” he told ICTMN. “From generations of knowledge and experience, people have learned how to live in peace and harmony with each other and the earth.

Another signer of the spiritual declaration is Sundance Chief Charles Scribe, president of the All Nations Traditional Healing Centre in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Cree healer told ICTMN that energy companies' quest for money and resources show that business leaders have lost sight of what's really important.

“It's all about making huge profits,” he said. “The spirituality is missed out. For years, our elders kept telling us there's a crisis occurring. We're living in an era that's explosive, like a time bomb. Our people believe that water is life-giving. With [these pipelines], if there's any type of leakage in any form, it destroys the water. Of course, a lot of water is being used to produce the oil, and it's creating a lot of pollution. The way things are going right now, we're headed for destruction—total destruction—for all people, not just First Nations.”

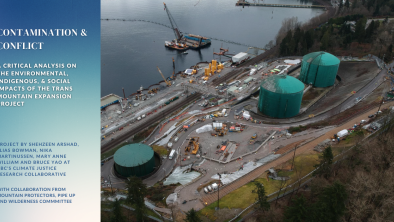

Photo: Rueben George speaks to the crowd about the threat of oil spills on unceded Coast Salish territory, during the Save the Salish Sea Festival, Sept. 2012.