Submission to the proposed logging operations in Algonquin

Friday, January 22, 2021

Re: Review of Proposed Operations for the 2021 – 2031 Forest Management Plan for the Algonquin Park forest

Dear Algonquin Forest Planning Team,

The Wilderness Committee (WC) is a national charitable organization committed to the protection of wilderness, wildlife, public lands and waters and climate. The WC welcomes this opportunity to comment on behalf of our organization and our supporters on the latest phase of the 10-year FMP planning for the Algonquin Forest.

Having inspected the published maps, tables and text for the Draft FMP and proposed operations, the WC maintains the position, expressed in our submission to the LTMD review, that commercial logging of any type is not an appropriate activity for Algonquin Park and should be phased out.

The goal of Ontario’s park system is to maintain and anchor ecological values in Ontario and this is done by requiring all protected areas be managed for ecological integrity as the first priority, regulated under the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 (PPCRA). The reason industrial activity such as logging and mining is banned in all other Ontario provincial parks is due to the recognition that these activities, no matter how carefully

executed, are incompatible with the intent of the PPCRA of upholding the public interest in ecosystem and biodiversity protection.

WC’s view is that the Algonquin Park Management Plan should be reviewed and updated to reflect provincial and national park standards throughout Canada prior to approving a 10-yr operational logging plan that will continue to cause significant negative environmental impacts. The absence of a meaningful plan to identify and monitor these impacts over the next ten years puts the ecological integrity and biodiversity in Algonquin Park at severe risk. In fact, the Office of Ontario’s Auditor General, Value-for-money audit: Conserving the Natural Environment with Protected Areas, finds that the 65% of Algonquin open to logging does not meet national standards for protection. The audit also finds that Ontario is failing to meet commitments to increase the number of protected areas. If all of Algonquin Park were protected, it would increase the total provincial protected area coverage by about 0.5%.

The exception that allows logging in Algonquin does not exempt forest managers from prioritizing ecological integrity. Our comments in this submission identify several issues in the proposed operations for 2021-31 that we believe illustrate unacceptable compromises that undermine this prioritization within the logging plans for the Algonquin Forest. While we offer recommendations toward the FMP to alleviate the most pressing issues, this should in no way imply that we condone continued commercial logging in the park. Instead, our recommendations are submitted as proposed first steps to take in a process to phase out commercial logging operations in Algonquin Park.

We appreciate your attention to these issues and expect that this submission will be passed on to all members of the Planning Team (PT) and the Local Citizens Committee (LCC) for consideration. We will also be submitting these comments to the Auditor General of Ontario, the Minister of Environment, Conservation and Parks, and the opposition critics for the Environment.

ISSUE 1. Operations Proposed in Old Growth Forests

a. Old-growth and logging in Algonquin

Old-growth forests provide unique habitats, mitigate against extreme conditions like floods and droughts and there is abundant evidence that they store more carbon than younger forests. (See for example

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259766087_Rate_of_tree_carbon_… ases_continuously_with_tree_size and https://e360.yale.edu/features/why-keeping-mature forests-intact-is-key-to-the-climate-fight)

According to Ancient Forest Exploration and Research (AFER), a scientific non-profit, Algonquin Park contains 40% of the old forests (>150 years old) in central Ontario while taking up just 4% of the land area. AFER has identified potential remaining old-growth stands from the Forest Resource Inventory, representing at least 24,000 ha. https://savealgonquinoldgrowth.org/maps

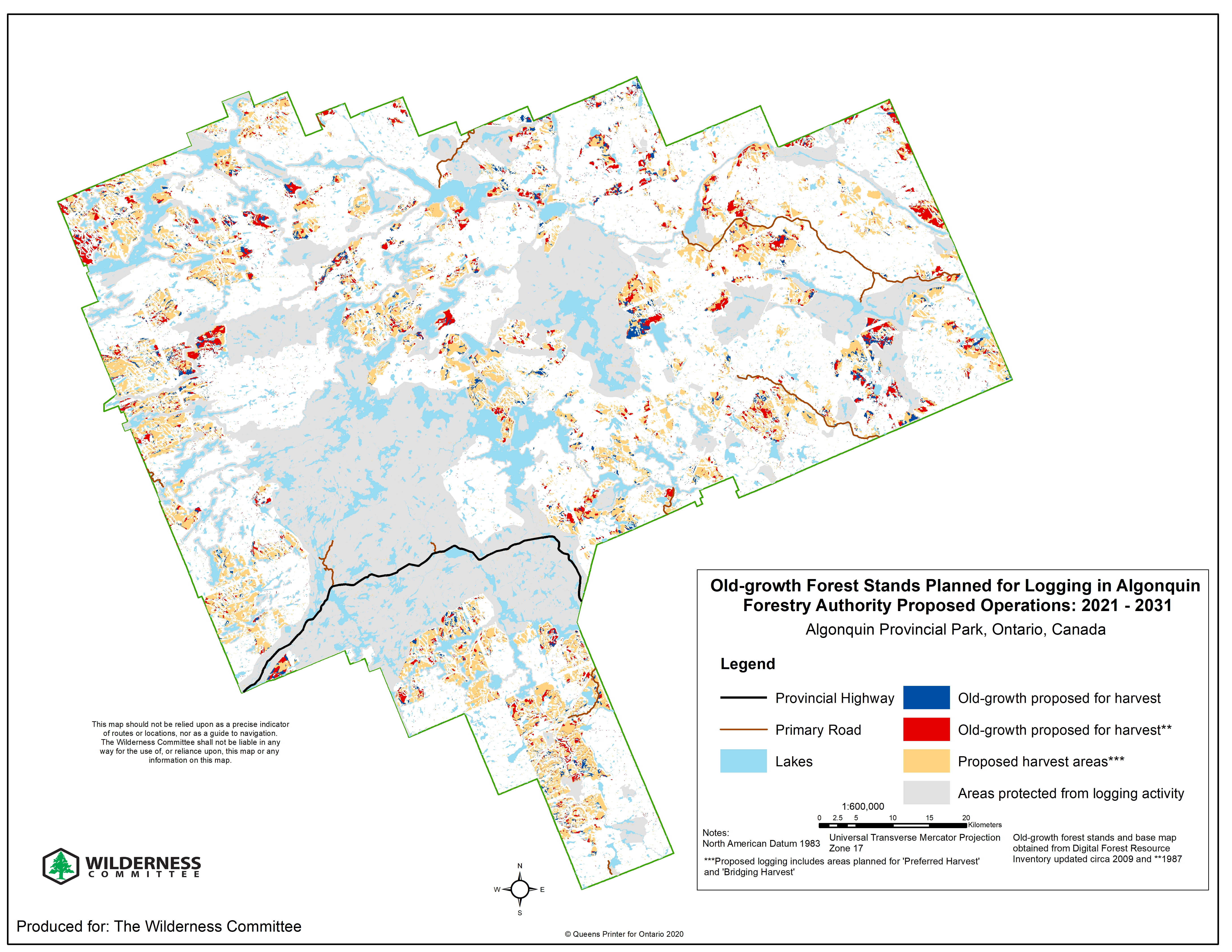

The Wilderness Committee has produced a map overlaying the AFA’s proposed preferred and bridging harvest areas for 2021-31 onto probable old-growth stands in the recreation/utilization zone of the park as identified by AFER. This map shows that from 7596 ha to 16, 871 ha (depending on FRI data used) of old-growth forest is slated for logging over the next 10 years. We submit that no logging of old-growth is acceptable if management for the ecological integrity of the Algonquin Forest is to be prioritized.

Large pristine landscapes dominated by old-growth forests are extremely rare in the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Forest region, and those that remain should be protected to preserve this natural heritage and conserve vital ecological functions. The remaining old-growth stands in Algonquin’s recreation/utilization zones consist mainly of hardwood forests dominated by sugar maple, yellow birch, hemlock, and other shade-tolerant species. These are relatively stable ecosystems that are not prone to frequent catastrophic disturbance such as a fire. The typical justification for logging of emulating natural forest disturbances that are otherwise suppressed does not apply in these cases. In the majority of hardwood forests, it is the wind that is typically the main agent of disturbance. Unlike fire, wind events are not subject to human intervention and presumably are operating more or less at natural levels. Logging, including selection harvest, reduces the average stand age and prevents these forests from achieving their ecological potential as old-growth. (http://www.oldgrowth.ca/algonquin/).

b. Old-growth and climate change mitigation

Our submission to the proposed LTMD expressed concerns about a lack of detailed plans for climate change mitigation. In response, the Planning Team referred to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) conclusion that “a sustainable forest management strategy aimed at maintaining or increasing forest carbon stocks, while producing an annual yield of timber, fibre or energy from the forest, will generate the largest sustained mitigation benefit” (From response letter emailed from Joe Yaraskavitch Sept. 18, 2020--No reference provided).

However, this justification for logging does not reflect the most up-to-date science in regards to old-growth and carbon storage. Current scientific literature increasingly suggests leaving old-growth forests unlogged is the best way to maximize carbon sequestration. Ecologist Mike Henry provides a review of the leading science for this claim at

http://www.oldgrowth.ca/algonquin/. WC suggests the Planning Team familiarize themselves with the references provided there as well as those provided above.

The PT should also refer to the latest IPCC report (5th Assessment) on Land Use and Climate Change (January 2020) which acknowledges that leaving intact forest ecosystems has more immediate impacts on climate mitigation, while other options, such as reforestation take decades to deliver measurable results. This should be taken in context with the primary message from the Fifth Assessment Report which is that “the scientific case for urgent action on climate change is clearer than ever. We have very little time before the window of opportunity to stay within 2°C closes forever but we still have that opportunity”

(https://www.ipcc.ch/2020/08/31/st-30th-anniversary-far/). With this acknowledged urgency it is incumbent on all land-based planning to identify the most immediate and cost-effective best practices for keeping carbon locked up over the next decade.

We submit another recent study that substantiates this claim:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2019.00027/full. This study states that while “the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change identifies reforestation and afforestation as important strategies to increase negative emissions, they face significant challenges [...] neither strategy can remove sufficient carbon by growing young trees during the critical next decade(s). In contrast, growing existing forests intact to their ecological potential—termed proforestation— is a more effective, immediate, and low-cost approach that could be mobilized across suitable forests of all types”.

Furthermore, we submit a 2020 report by the Chair of the World Commission on Protected Areas Climate Change Specialist Group, “Enhancing Canada's Climate Change Ambitions with Natural Climate Solutions” which identifies targeted protection of Ontario’s remnant temperate old-growth forests as part of the top recommendations for effective nature-based climate solutions to 2030. The study specifically calculates that the unprotected old-growth forests in Algonquin store 4.8 Mt of carbon.

c. Lightening the Ecological Footprint of Logging requires protecting old growth.

In 2005, when the Provincial Parks Act was under review the Minister of Natural Resources asked the Ontario Parks Board to provide advice on how to “lighten the ecological footprint” of logging in Algonquin Park. In 2006 the Ontario Parks Board submitted a proposal to the Minister that included an increase of protection from 22% to 54%

https://www.algonquinpark.on.ca/pdf/lighteningthefootprint_recommendati…

This proposal was rejected by the Minister and a joint proposal of the Ontario Parks Board and the Algonquin Forestry Authority that increased protection to only 35% of the Park was accepted. This joint proposal emphasized protection of recreational canoe routes but added very little to the Nature Reserve and Wilderness zones of the Park. Even the 200-meter buffer around high use canoe routes was narrowed to 120 meters in many areas as a concession to the forest industry. The joint proposal also failed to identify and protect large tracts of pristine old-growth forest. While the joint proposal reduced the impact of logging on recreation in Algonquin Park, it failed to adequately reduce the ecological footprint of logging in the Park. It is high time that the intentions of the “lightening the footprint” review were fulfilled, and that means first and foremost protecting old growth.

Recommendations

• Confirm the remaining old-growth stands in Algonquin such as those identified by AFER https://savealgonquinoldgrowth.org/maps and begin a process towards adding them to the Nature Reserves and Wilderness Area of the park. In the meantime, follow the precautionary principle and remove these old-growth areas from proposed operations.

• 120-meter buffers around canoe routes should be expanded to 200 meters, particularly if the buffer includes pristine or old-growth forest.

• Carbon accounting should prioritize leaving intact old-growth forests as important carbon banks.

ISSUE 2. Ecological Impact of Proposed New Primary and Branch roads

Road building has perhaps the greatest impact of all logging activities in proportion to the area devoted to it through the following:

• increased risk of facilitating inappropriate access and abuse of irreplaceable resources • Increased deforestation

• increasing avenues for invasive species and predators

• soil compaction and erosion

• habitat fragmentation

• Associated aggregate extraction and risks of water contamination.

An estimated 6,000 km of logging roads crisscross the park. With a majority facilitating single-tree selection harvesting and being reused every 20-30 years, they are effectively permanent. This has negative impacts on carbon storage, hydrology and some wildlife species.

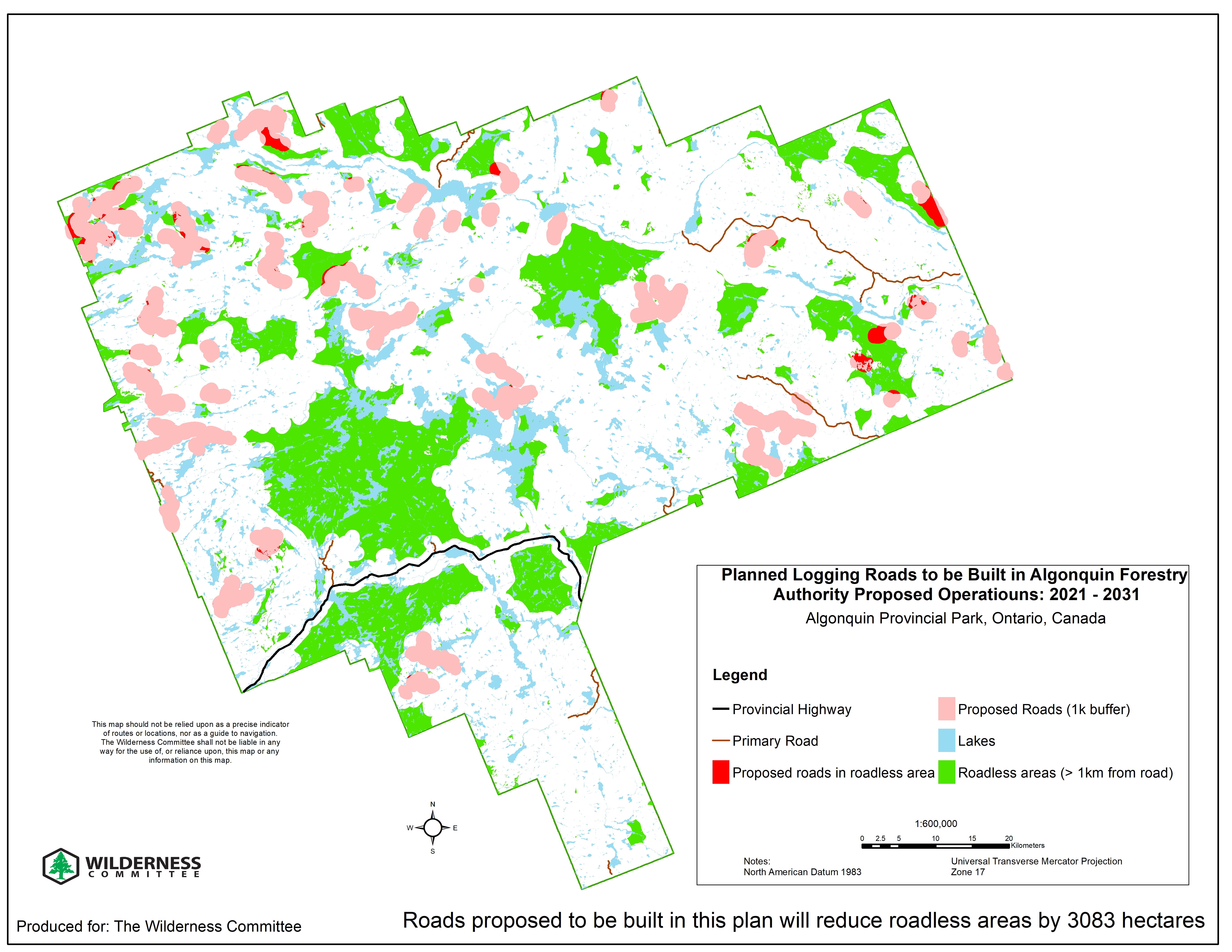

The map below portrays the proposed new primary and branch roads (From the Summary Map Draft FMP-- Sum 00.pdf) as well as identified roadless areas of the park (RAs). RAs were determined as areas at least 1 km from a known road.

This map reveals that the proposed new road-building will reduce the roadless areas by 3083 hectares. All new roads have negative impacts on the ecological integrity of the Algonquin forest by reducing forest cover, but road construction in roadless areas is especially egregious, as they permanently reduce the amount of the forest that is least impacted by human disturbance.

Recommendation:

• The FMP should focus on avoiding forest cover loss due to road construction and restoring already degraded roads, landings and aggregate extraction to more natural forest cover

• All roads that diminish the amount of roadless areas should be removed from proposed operations.

ISSUE 3. Logging Operations and Species-at-Risk (SARs)

a. Forestry Prescriptions under CFSA for SARs do not achieve requirements to protect and recover under ESA

The Wilderness Committee submits that commercial logging operations in Algonquin do not meet the requirements under the province’s Endangered Species Act (ESA, 2007) to identify and prioritize actions to protect and recover threatened and endangered species and their habitat. This represents another instance of ecological integrity not being prioritized in these management areas. While the Crown Forest Sustainability Act (CFSA) requires that FMPs “have regard for” plant and animal life, and Areas of Concern (AOC) prescriptions are meant to “minimize” or “mitigate” harm to species-at-risk (SARs), this is a much lower bar than the legal requirements to protect and recover under the ESA-- and unacceptable in a provincial park.

When forestry operations were originally temporarily exempted from compliance with the ESA in Ontario the intent was to give the industry time to adjust operations to meet the more stringent requirements under the ESA as compared to the CFSA. The Ontario government recently approved a permanent exemption for forestry without providing evidence that such adjustments had been achieved, nor were any changes to species-at-risk protection under CFSA made. The Wilderness Committee expressed concerns about this exemption in our submission to the proposed LTMD. The response from the Planning Team was that “a full assessment of how ESA requirements compare to CFSA protocols has already been completed” (From response letter emailed from Joe Yaraskavitch Sept. 18, 2020). When we asked for more details on where to access this assessment we were directed to the ERO listing for permanent exemption at https://ero.ontario.ca/notice/019-1020. However, we were unable to find any such comprehensive assessment nor anything to assure us that such a comparison found the same levels of protection under CFSA and ESA.

b. Insufficient monitoring of the effectiveness of AOCs to protect and recover habitat

As described in FMP Table 10, “Assessment of Objective Achievements”, the only indicator given for the CFSA criterion to “protect the habitat of forest-dependent species at risk” is “compliance reports through Forest Operations Inspection Program--the number of not-in compliance reports related to SAR wildlife and AOC prescriptions” (From Draft FMP Tables accessed through https://nrip.mnr.gov.on.ca/s/consultation

notice?language=en_US&recordId=a0z3g000000oWBJAA2)

The Wilderness Committee submits that this compliance/non-compliance indicator is an insufficient assessment to ensure that the ecological integrity of SARs habitat is prioritized in management of the recreation/utilization zones in Algonquin Forest. Inspections and compliance reports merely describe whether AOC prescriptions were followed. No assessment or analysis is required to determine whether prescriptions were demonstrably effective in mitigating harm, much less whether they were effective in protecting and restoring habitat.

As an illustration of this concern, here is a statement from the Year 9 Annual Report from AFA regarding mitigation efforts on logging roads in the park: “In some situations, such as Species at Risk habitat, roads are more aggressively bermed and portions rehabilitated after operations to ensure critical areas are not affected by unauthorized access. These measures are effective.” (p. 7, Year Nine Annual Report, AFA accessed through

https://nrip.mnr.gov.on.ca/s/fmp-online?language=en_US). Not only is it concerning those roads are permitted to be built in recognized species-at-risk habitat at all, but the statement that mitigation measures are “effective” fails to offer any evidence or data to support such a conclusion. Nor does it include the criteria upon which “effectiveness” is or would be evaluated. Perhaps this is sufficient for other areas of Crown forest logging, but not in a provincial park, where ecological integrity is meant to be the priority.

c. Methods for identifying AOCs for SARs habitat

FMP-11 within the Draft Table document outlines the “Operational Prescriptions for Areas of Concern and Conditions on Roads, Landings, and Forestry Aggregate Pits''. While AOC prescriptions are provided for some SARs habitat in Algonquin--such as suitable hibernacula for Hognose and Milk Snake, suitable breeding habitat for Red-Headed Woodpecker, suitable habitat for Pale-Bellied Frost Lichen, habitat for Flooded Jellyskin, Whip-poor-will defended territory and suitable breeding habitat for Canada Warbler), there are no prescribed methods for actively surveying for and identifying these SARs habitat, nor could we find such methods in other sections of the proposed operations. Similarly, the Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Level provides prescription details for minimizing harm to species and habitat but provides no methods within forestry operations for identification of these types of AOCs.

The apparent lack of methods for identifying habitat and suitable habitat for SARs is concerning. It is unclear, for example, whether a full survey for these AOCs has been undertaken prior to the identification of areas for new operations, primary and branch roads and aggregate extraction.

Our concerns around the monitoring of the effectiveness of AOCs and assessment of SARs habitat are supported and augmented by the recent audit report published by the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario entitled “Value-for-Money Audit: Setting Indicators and Targets, and Monitoring Ontario’s Environment” (Nov. 2020). As the report acknowledges, effective environmental protection requires establishing targets, monitoring the environment and analyzing collected data. The overall conclusion of the audit, however, was that “the Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture ministries do not have effective systems and processes for setting targets, carrying out effective monitoring practices, and ensuring data quality and data sharing for certain aspects of Ontario’s environment”(p. 5). In particular, to SARs, the audit found the following:

• The Natural Resources Ministry has not fulfilled a commitment to establish a long-term, broad-scale program to monitor Ontario’s biodiversity

• Monitoring protocols and programs have not been developed for several endangered species

• Monitoring in Ontario’s protected areas is not required or consistent.

• The Environment Ministry and Natural Resources Ministry do not have standards or direction for the required content or format of their monitoring protocols

• Few environmental monitoring programs are evaluated to ensure that they are effective

These deficiencies in biodiversity monitoring present a risk to the goal of management for ecological integrity even in protected parks and conservation reserves where the industry is banned and ESA regulations are the law. In the Algonquin Park recreation/utilization zones where logging, road building and aggregate extraction is permitted and where the forestry is exempt from ESA regulation, the risk is surely compounded.

Recommendations:

• Commit to protecting and recovering species at risk and their habitat according to the Endangered Species Act (2007) and not merely minimizing harm as required under the CFSA.

• Make publicly available the procedures, protocols, and timelines used to identify, track and monitor all SARs populations as well as suitable habitat for SARs within the recreation/utilization zone

• Develop and make public protocols for assessing the effectiveness of AOCs. • Fully assess proposed new roads and aggregate pit areas for suitable SARs habitat prior to commencing building operations. Where suitable habitat is identified, refrain from building.

• The MNRF, in cooperation with MECP should produce a comprehensive environmental assessment of the impact of logging operations in Algonquin Park on species-at-risk.

ISSUE 4. Algonquin Park Management Plan is Past Due for Review

Under the PPCRA, park management plans are required to be reviewed and re-written every 20 years. As noted by the Office of the Auditor General report from November 2020, the review of Algonquin Park’s management plan is over 2 years overdue. While we understand that this is not within the purview of FMP planning, we urge the Planning Team and the MNRF to work within their sphere of influence to encourage the MECP and Parks Ontario to move forward with a process, including public consultation, for a thorough review of the Algonquin Park Management Plan.

Thank you for your attention and consideration,

Sincerely,

Katie Krelove | Ontario Campaigner

Wilderness Committee

#207-425 Queen St. W

Toronto, ON, M5V 2AS

Phone: 647-208-4026

Email: katie@wildernesscommittee.org