Tar Sands Oil Producers Eye California

New America Media

SAN FRANCISCO -- The Obama Administration’s recent decision to delay the approval process for the controversial Keystone XL pipeline has shifted attention to alternate routes for bringing a glut of tar sands oil in Canada to refineries and ports abroad.

Last week, Canadian firms bought up thousands of miles of existing pipeline in the U.S. Midwest, intending to reverse oil flows southward to Gulf Coast refineries – a “workaround” that would get oil flowing in the right direction, but still not enough to accommodate the volume of crude being produced.

A second – lesser known -- alternative involves piping tar sands oil westward across Canada to Vancouver, where it would reach West Coast refineries by tanker. California, which up until now has remained out of the fray in the fight over tar sands oil, would be key to such a northern pacific route.

“California is the prize,” said Greg Karras, senior scientist with Oakland-based Communities for a Better Environment. “It’s where the [Canadian tar sands] industry is going. They have this gigantic reserve of fundamentally dirtier oil that they want to exploit, sitting above the best refining country in the world.”

The Golden State is well-positioned to take in tar sands oil, a heavier, lower quality crude that requires intensive processing, Karras said. Its oil refineries, in the last few years, have undergone upgrades to process heavier crude, and the state’s ports provide an easy gateway to Asia.

California’s sources of crude from within the state and Alaska are dwindling, leading to increased reliance on imports of heavier forms of crude to meet demand. The state currently imports half of its crude from the Middle East and Latin America, according to Karras, and that number could grow to three-fourths in the next 10 years.

Severin Borenstein of UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and co-director of the UC Energy Institute says the preferred outlet [for Canadian tar sands oil] is through the Midwest, because oil can be piped directly to refineries.

“If it’s sold through the Pacific, it’s more likely to end up in California refineries,” he said. “[Delaying] Keystone XL is not going to stop it from getting produced, it just changes the direction it flows.”

There’s no direct way for tar sands oil to get to California at the moment, says Steve Kretzmann, who heads Oil Change International. He said the West Coast option involves two pipelines – the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline and the expansion of the existing Kinder Morgan-owned Trans Mountain pipeline, but both these routes face significant hurdles.

“The first barrier they will have for that is the increased tanker traffic around Vancouver. Other than that, there’s no direct route,” he said.

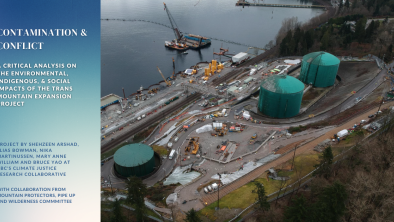

The planned expansion of the existing Kinder-Morgan owned pipeline is intended to more than triple the 80 tankers of crude sailing out of Vancouver harbor for foreign refineries and markets, according to Ben West, healthy communities campaigner with the Vancouver-based Wilderness Committee.

He said the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline is currently going through the government’s approval process, with an environmental assessment and public comment period expected in January.

If approved and once up and running, the pipeline, which would extend to the Pacific Coast from Alberta, would supply half a million barrels a day, according to a Reuters report.

The Northern Gateway pipeline faces fierce opposition, West says, with thousands of people already signed up to speak at public hearings. The project has Canadian environmentalists up in arms.

“It’s a huge project that would span from Alberta to British Columbia, and would have to go across the Rocky Mountains,” West said. “It will cross a thousand streams, many of them salmon-bearing streams, and the headwaters for major river systems, like the Fraser River. Any spill would be utterly devastating.”

The project would involve clear-cutting forests in British Columbia, and jeopardize the Great Bear Rainforest, an ecologically-sensitive area, he said.

“Canadians want to play a responsible role in the world. We’re concerned about the growth in tar sands’ dirty source of [fuel],” said West. “In Canada, 80 percent [of the public] say climate change is the most serious issue. At the same time, the oil industry is an important source of revenue here.”

West says he believes Canadians and Americans on the West Coast share similar progressive values, and he sees growing cooperation between citizens of the two regions critical to prevent the Pacific from becoming the “gateway to global warming.”

West says tar sands crude from Canada is already reaching California.

The Wilderness Committee recently launched an oil tanker tracking system, where subscribers to the service can receive updates via cell phone and Twitter on oil tankers in Vancouver’s (Burrard) Inlet. According to the group’s website, it started the service to better track increased tanker traffic from the Kinder-Morgan owned pipeline without the public’s consent or knowledge.

Prior to launching the system, West says, he tracked oil tanker traffic through public databases such as www.marinetraffic.com that can track a vessel’s position through automated identification systems and GPS-collected data.

He documented how most of the tankers leaving Vancouver eventually ended up in California.

“From Vancouver terminal, the oil heads to California on tankers to refineries in Richmond and Long Beach,” he said.

Tar sands, or oil sands, is a mixture of sand, other minerals, water and a dense form of petroleum – bitumen -- that resembles tar in appearance. Like tar, it doesn’t flow easily and requires extreme heating via steam injection to extract. Intense energy is required, giving the crude a carbon footprint that is 10-20 percent greater than other oil, according to UC Berkeley’s Borenstein.

Refining tar sands is also more carbon intensive, because it takes more energy to process the lower quality, heavier crude into a cleaner formulation of fuel that is mandated in California.

It is the tar sands large carbon footprint that could doom its long term viability in the state, says Dr. Simon Mui, a scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

California’s low carbon fuel standard requires fuel providers to reduce the carbon footprint of fuel by 10 percent by 2020, Mui said. It recently took effect and could become even more stringent in December, taking into account the full life cycle of emissions.

Mui says the standard doesn’t ban tar sands, however.

“It doesn’t’ stop them from necessarily using this, but it makes it much less economic for refineries to take on these crude oils and expand using them,” he said. “Because, California is accounting for the upstream emissions wherever they occur.”