Spotted Owl: Spirit of the Ancient Forest

Read the PDF version by clicking here.

THE FINAL FIGHT. THE ELEVENTH HOUR. TAKE A STAND FOR THE SPOTTED OWL.

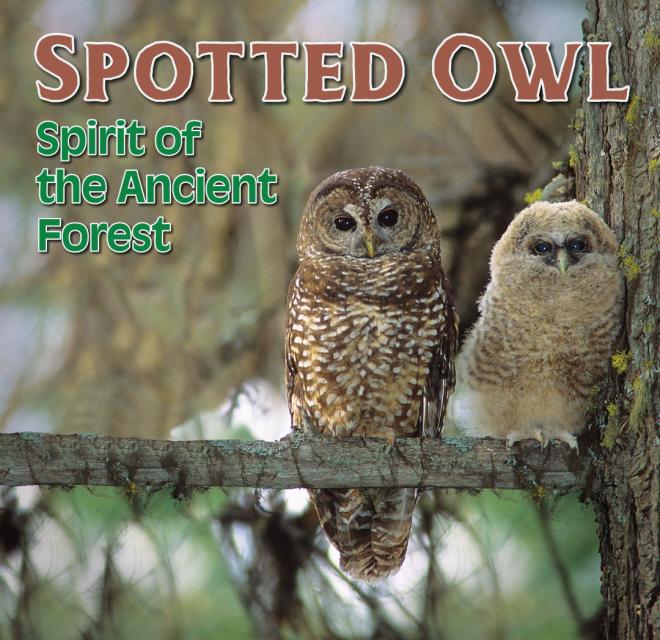

With a wingspan of up to four feet (121 centimetres) but weighing a mere one and a half pounds (680 grams) on average, piercing dark eyes nested in defining facial disks of feathers, and not surprisingly covered in white “spots,” the northern spotted owl is a species of legends. Mating for life, each pair of spotted owls needs a large territory of its own for hunting and nesting, building nests in natural snags and hollows of the oldest trees that give lots of shade and have good perches for roosting.

Spotted owls once thrived in the old-growth forests of southwest mainland British Columbia, nesting in centuries-old Douglas fir, western hemlock and western red cedar trees. Once numbering 500 pairs prior to the arrival of settlers, the spotted owl is following the course of more than 30 wildlife species that became extinct in Canada as a result of colonization and out-of-control industrial activities.

Only three spotted owls are left in the wild in Canada. Two of them are a breeding pair.

📢 Give a hoot: Take action for spotted owls

Spô’zêm (Spuzzum) Nation, whose territory is one of many that provided a home to the owls since time immemorial, regard the spotted owl as a “messenger between this world and the Spirit World. The message of their extirpation both symbolizes and prophesizes our environmental crisis.”

That message is loud and clear, here and around the world — we are facing a mass extinction crisis.

A long-time economic reliance in Canada on the production and export of large amounts of raw natural resources has had and continues to have a devastating impact on wildlife habitat. This includes logging, fishing, mining, oil and gas and agriculture.

Canada has been built around the dispossession of the Indigenous people who’ve always stewarded the lands and waters here. The violation of Indigenous rights, the exploitation of ecosystems and resources and the impacts on biodiversity go hand in hand.

Weak federal, provincial and territorial enactment and enforcement of laws to protect species have allowed this crisis to grow. Canada has a federal Species at Risk Act which provides some protection for species, but not nearly enough. B.C.’s provincial government promised in 2017 to enact a provincial species at risk protection law — but in 2020 reneged on their promise.

Today, at-risk wildlife needs champions. The newest champions may just be that last breeding pair of wild spotted owls who’ve refused to give up and who’ve produced chicks two years in a row. Their determination to live is an inspiration to wildlife defenders everywhere.

We must join them and demand the governments of Canada and B.C. step up and take responsibility for their protection, and return management of these lands to Indigenous communities. The battle over protecting this old-growth forest wildlife habitat from industrial logging is reaching a critical moment — and it’s a battle we can win.

HOW TO PUSH A SPECIES TO EXTINCTION

Every spotted owl in Canada is in southwest mainland British Columbia. Its range extends from east of Vancouver north to the village of Lillooet and as far south as the U.S. border. In fact, the majority of spotted owl range is in the U.S., located in old-growth forests found in Washington State, Oregon and northern California.

Concern over steep declines in spotted owl numbers in the mid- 1980s caused wildlife managers in Canada and the U.S. to plan measures to halt the population drop.

In the U.S. almost ten million acres of forests were eventually protected from logging. In Canada, attempts to rein in B.C.’s powerful logging industry went nowhere and logging of the owl’s old-growth habitat continues full speed ahead.

Prior to the start of industrial logging in the late 1880s, an estimated 500 pairs of spotted owls called southwestern B.C. their home. By 1991, biologists found the surviving population had declined to 100 pairs due to ongoing logging of the owl’s old-growth forest habitat. In 2002, the estimate was 30 pairs. Five years later only 19 spotted owls were found.

Today biologists have only been able to find three remaining owls, two of them form the last surviving pair.

A lack of provincial species at risk legislation, delays in federal government mapping of their critical habitat, and continued logging by the provincial government’s own logging company, BC Timber Sales and private logging companies, make their survival seem impossible.

Yet against all odds, these last three owls endure and the pair have produced baby chicks two years in a row. Because people didn’t give up on them. Environmental groups in B.C. continue to strive for their survival. Indigenous communities such as Spô’zêm First Nation are leading the fight.

Now, the governments of Canada and B.C. have been brought to the table to work with First Nations towards protecting the owl’s remaining forest habitat. Which makes now a critical time to ensure they hear from all of us loud and clear. There are hopeful examples of species in dire straits coming back to healthy numbers, like the story of the sea otters off the Pacific coast of North America. Today they thrive. That too can be the future of the spotted owl.

THE LAST SPOTTED OWL FORESTS

CAGED

In 2006 the B.C. government initiated the Northern Spotted Owl Breeding Program. They captured some of the last remaining wild spotted owls and stuck them in cages. Their goal was to produce a supply of captive-bred young owls for reintroduction into their old-growth forest range.

They committed to providing adequate funding to support their plan of raising and releasing about 20 owls per year into the wild for a total of 240 owls by 2021, as their way of addressing spotted owl extinction. There are currently 28 spotted owls in captivity, including seven breeding pairs.

The problem is over the past 15 years exactly zero owls have been released back into the wild. None.

Perhaps that’s due to the government underfunding the program so badly it’s constantly seeking public donations to scrape by. Or since the government hunted down and captured some of these last wild owls, they’ve continued to issue logging permits to cut down more and more old-growth forest habitat — about 1,400 hectares per year on average. And the worst offender is BC Timber Sales, the government’s own logging company.

The only way this captive breeding program will stop being a macabre spotted owl zoo is for the B.C. government to keep their promise to fund the work necessary and release owls into the wild to survive and thrive. That requires an increase in funding, an immediate end to logging and permanent protection of spotted owl old-growth habitat. It’s time to set the owls’ on their path back home.

UNDER THE OWL’S WINGS

Sharing the spotted owl’s forest habitat are a number of other at-risk species. Their fate also rests in stopping the logging of remaining old forests and protecting second-growth forests so they can grow to become suitable habitats once again.

Birds like the marbled murrelet and coastal western screech-owl, listed under the federal Species at Risk Act as threatened, require healthy old forests to survive. They are joined by amphibians like the coastal giant salamander, listed as threatened and the coastal tailed frog, listed as special concern.

Then there are species outside these forests who also need them to survive. Central among these are the wild Pacific salmon reliant on ancient forests to stabilize stream banks and provide shade and water filtration for their spawning beds and rearing pools. Their populations have declined dangerously due in part to industrial logging.

Grizzly bears, northern goshawk, cutthroat trout, martens, fishers, pileated woodpeckers, harlequin ducks, hooded mergansers and flammulated owls are also members of the long list of species that will benefit from preserving the old forest habitat of the spotted owls. These are just some of the beautiful wild creatures living under the owl’s wings.

STOLEN LANDS

Within the range of the spotted owl are the territories of about 50 Indigenous communities representing several Salish languages including Halq’eméylem, N?e?kepmxcín, Sƛ’aƛ’imxǝc, SEN?O?EN and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh. Since ancient times much of these territories were blanketed by old-growth forests.

From these forests clean water flowed, providing drinking water and a home for the many runs of salmon and other fish that fed the people. Red cedar trees provided material for house building and canoes. Every tree, plant and creature in the old-growth forest helped to make the lives of the people better. Old-time stories handed down from generation to generation are often vivid accounts of long-ago when humans, spirit beings and wild creatures could communicate with each other and weren’t seen as so different from one another as they seem today.

(WC files).

But starting in the mid 19th century, settlers with little knowledge of the local history, ecology, traditions, laws, spirituality or expertise began to pour into these Indigenous territories. Soon after, the uninvited newcomers began to build towns and cities, clearing forests as they went. A growing trade based on the production of logs plundered from clearcutting stolen old-growth forests became an economic mainstay of the new settler communities.

Huge swaths of forests were cut down along the Pacific Coast, up the Fraser River Valley and eventually up most of the tributary valleys. Today, only a remnant of the original old forests remain, but government and industry still target them relentlessly. It’s in these forests that lies the hope of survival for at-risk species like the spotted owl.

Spô’zêm Nation territory (WC files).

These forests, and management of them, must be returned to the original and rightful owners who have lived with them far longer than the thousand years it takes a big red cedar tree to reach old age. Compared with the old-growth forests in spotted owl habitat Canada, formed in 1867, is a mere sapling under the shade of ancient giants.

Governments of Canada and British Columbia have a duty to work with Indigenous nations on conservation planning and long-term management and ensure species and forest habitat protection is properly funded and backed up by strong species legislation.

FOREST HOMES CAN’T BE REPLACED

A single pair of adult spotted owls needs a home territory of 2,800 to 3,400 hectares of old forests. Given the average size of a sports field is one hectare, owls need a lot of space.

They need big, old trees to find a good nest site, favouring the broken tops of centuries-old Douglas-fir. Deep dark forests to hide from predators like the great horned owl or competitors like the barred owl. Shade from the canopy to cool them from the hot summer sun and block the cold winds of winter. Old-growth trees with good spacing to fly through the canopy at night in the hunt for their preferred prey — flying squirrels and bushy-tailed woodrats. After young spotted owls leave their nest to look for their own territory, they need connecting corridors of old-growth forest for safe travel.

This last part is why spotted owls have declined so drastically. Young owls haven’t been able to safely navigate through clearcuts and tree plantations, avoiding predators and starvation, to find new territory and a mate. There aren’t many mates to find these days, especially since B.C. began capturing all the wild owls they could get their hands on.

The good news is suitable old-growth forests still exist in the owl’s range. There are still 533,306 hectares of suitable old-growth forest habitat remaining, with 151,428 already preserved in parks and protected areas, and a further 66,919 hectares protected in Wildlife Habitat Areas, designated to put spotted owl habitat off-limits to logging.

However, the remaining 314,959 hectares is still open to industrial logging, without any concern for spotted owl survival. This forest must be protected from logging now. Additional second-growth forests must be protected to fill in the habitat gaps created by an insatiable logging industry that’s consumed far too much.

By moving forward quickly to designate a network of new Indigenous protected areas, wildlife conservation areas and places important for outdoor recreation within spotted owl range, the governments of B.C., Canada and First Nations can create an expanded protected area system capable of saving endangered wildlife. In doing so, we preserve the natural spaces and species we want to pass down to future generations.

It is nothing short of a miracle two owls have survived, eluded capture, found each other and produced young two years in a row. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to look back one day and realize the last pair of wild spotted owls united us in the quest to turn around habitat loss and species endangerment because of their inspiring story and will to survive?

SPIRIT OF COOPERATION REQUIRED

Three last remaining wild spotted owls in Canada currently reside within the territory of the Nlaka’pamux community of Spô’zêm First Nation. The Nation has demanded the B.C. government cease logging in their territory immediately to give the surviving owls a chance at life.

Sadly, the B.C. government has continued year after year to issue logging permits in Spô’zêm Nation territory and elsewhere throughout the spotted owl’s range. B.C.’s ongoing liquidation of forests is propelling a continuous death spiral for spotted owls and other creatures that have lived in these forests for millennia.

The Wilderness Committee, represented by Ecojustice lawyers, teamed up a number of times in the past in court challenges against logging companies and the governments of Canada and B.C., in a bid to get more spotted owl habitat protected. Those battles put pressure on both governments, resulting in tens of thousands of hectares of old-growth forests designated as Wildlife Habitat Areas, some of which are off-limits to logging.

However, until now logging of old-growth forests outside the protected Wildlife Habitat Areas hasn’t slowed down. Consequently, the footprint of logging continues to spread with a deadly disease of logging roads, clearcuts and tree plantations.

Recently we partnered again with Ecojustice and put the federal government on notice. Unless Canada enforces the Species at Risk Act to map and protect all of the spotted owl’s remaining critical habitat, we will take them to court once again. The federal government responded by committing to complete the long-awaited critical habitat mapping process for the spotted owl this year. They’ve reached out to B.C. and First Nations, including Spô’zêm Nation, to cooperate on habitat protection.

In the face of such strong support for habitat protection from the Spô’zêm Nation, B.C. has committed to halting logging in the valleys where the last owls live.

Partnership among these three governments presents a once in a lifetime opportunity for the last wild spotted owls. A cooperative habitat protection plan must quickly deliver new protected areas, including Indigenous protected areas, and strengthen protection within existing Wildlife Habitat Areas.

Swift and strong actions are required to bring back spotted owls to healthy numbers and ensure the survival of all the at-risk creatures who share these ancient forests. This inclusive, cooperative and timely action to protect endangered habitats and species, while respecting First Nations’ governance, is the way forward for species at risk across Canada.

TAKE ACTION: Give a hoot for the owls