Turning back the clock on extinction

THE TRAIL TO A FLOURISHING PLANET

Even the most carefully placed footsteps are too loud in caribou country. The lichen-covered forest floor gives you away before you can distinguish animals in the distance. Caribou, grizzly bears, wolverines, whooping cranes, cougars and wolves live here in the boreal forest.

Wildlife helps close the gap between modern societies and the ecosystems we’ve come to dominate and disconnect from. As species disappear, we lose this connection.

A stroll in the wild heightens your senses. You may find yourself unearthing lost feelings of connection to the land that have been suppressed for over 12,000 years. Wildlife helps close the gap between modern societies and the ecosystems we’ve come to dominate and disconnect from. As species disappear, we lose this connection. Being in the forest may no longer present the opportunity to walk in the footsteps of caribou or a fox and its kits. It’s devastating but that’s where we’re headed.

Across the lands now known as Canada, wrecked remains of habitats are a stark reminder of how wild creatures have been sacrificed in the name of resource extraction and corporate wealth. Rewinding the clock, we only have to go back 60 years to see when large-scale fossil fuel extraction, clearcuts and mining really began impacting wildlife across the country. The early 1900s is when industrial whaling drove many species to near extinction. Another 50 years back from then is when giant trees in B.C. — some of the largest on Earth — began to fall on an industrial scale.

The Western extractive resource economy built to serve twin systems of colonialism and capitalism hasn’t been around that long. But it’s been devastating for wildlife, ecosystems and the Indigenous communities from these lands and waters. Across Canada, the picture is bleak. We’re close to losing over 800 species forever and those that remain are getting fewer and fewer. The land is being emptied.

Throughout the country, it’s within the regulations to harm species. We’re often up in arms over century-old heritage buildings. Many jurisdictions have laws in place to protect older architecture but not to safeguard species millions of years in the making. There isn’t legislation that protects at-risk biodiversity and wildlife in most provinces and territories. Where those laws do exist, they’re weak. To mend the damage we’ve done, we must change the system that incentivizes destruction by implementing strong laws that protect biodiversity.

There are respectful ways to interact with the land and species that were in place long before European contact and colonialism. Indigenous communities have been living with caribou since time immemorial. In the Boreal, Indigenous communities have strong relationships with caribou, depending on them for everything from meat and furs to tools. In the past, Mountain Métis near Grande Cache, Alberta would burn the land to encourage plant growth to nourish ungulates, including caribou, and harvest them in a way so populations would thrive. However, since the 1970s it only took the industrial resource economy 50 years to push this species to the brink of extinction.

It’s possible to rebuild our relationship with the wild in a way that cherishes wildlife and respects the boundaries of this planet. We must start by returning lands and authority to Indigenous communities. However, in the absence of good laws that protect wildlife, Indigenous communities are often left alone at the forefront to protect their territories and wildlife from industrial projects. Efforts to protect wildlife must centre Indigenous sovereignty and justice while demanding change from the system that harms so many for the benefit of so few.

If every jurisdiction across the country had stronger laws to protect wildlife and ecosystems that aligned with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), we could ensure wildlife flourish.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE WORK OF A BILLION CREATURES

Biodiversity, or biological diversity, is the variety of living things. But more than that, it’s the water you drink, the food you eat and the air you breathe. Everyday life is made possible by the work of a billion living creatures, from bacteria and fungi to pollinators and trees. It’s more than an engaging wildlife documentary narrated by David Attenborough. Biodiversity increases the health, resilience and productivity of ecosystems and everything that depends on them, including us.

From the genetic to the ecosystem level, diversity is important. Cheetahs, for example, have low genetic diversity, which makes it hard for them to birth cubs. Species diversity is the number of different species within an ecosystem and the individuals within those species. In the boreal shield of Canada, wetlands harbour an impressive amount of biodiversity. Hectare for hectare, wetlands are some of the most productive ecosystems in the world, on par with tropical rainforests and coral reefs.

Ecosystem diversity combines the diversity of the living world, species and genetics, with the nonliving world, like land formations and the climate. B.C., for instance, has incredible biodiversity largely due to the variety of ecosystems, from mountainous environments, and desert-like landscapes to lush rainforests and marine ecosystems.

Biodiversity also protects us from disease. As humans encroach on wilderness, landscapes are destroyed, ecosystems are disrupted and viruses transfer from their natural hosts, where they find new ones — like humans. Ecosystem destruction tends to cause large-bodied species to disappear while smaller-bodied, fast-lived species that are famous for transmitting disease increase.

We should protect biodiversity for no other reason than its intrinsic value and because wildlife have a right to exist. But there are also thousands of reasons that align closely with human needs. Protecting biodiversity is essential.

RECIPES FOR EXTINCTION

Species on Earth are going extinct at least 1,000 times faster than would be the case without human influence. Currently, there are 809 at-risk species listed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). But biodiversity is more than just how many species exist. It’s also the number of individuals within each species — and those numbers are plummeting. Half of the monitored species in Canada experienced population declines by an average of 83 per cent between 1970 and 2014.

Most people are aware of the pressure we put on wildlife and ecosystems. When understanding extinction broadly, the causes and solutions become easier to understand. The five biggest drivers of the decline in nature we’re experiencing today in descending order are:

- Changes in land and sea use: 75 per cent of the Earth’s landsurface and 66 per cent of the marine environment has been altered by humans.

- Direct exploitation of organisms: Overexploitation of wildlife is driven by harvesting, logging and hunting. In marine ecosystems, shing causes the most harm, followed by land and sea-use change.

- Climate change: A small change in climate drastically impacts the ability for species to live. On the extreme side, it increases the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, impacting biodiversity.

- Pollution: Pollutants from heavy industry negatively impact soil, freshwater and marine water quality and the global atmosphere. Marine plastic pollution has increased tenfold since 1980, affecting at least 267 species.

- Invasive species: Nearly one-fifth of the Earth’s surface is at risk of plant and animal invasions, impacting native species and ecosystem functions.

We can address all five of these drivers. Policies to cease destroying nature and overexploiting organisms can and should be implemented immediately.

EXTINCTION ISN’T A CRIME IF THERE’S NO LAW AGAINST IT

When major industrial projects are proposed, concerns about wildlife and species at risk are rarely an obstacle. Provincial and territorial laws seldom require independent scientists to accurately assess the full impacts to wildlife. Even when projects undergo a wildlife assessment that concludes there will be significant harmful effects to at-risk wildlife, the projects are rarely stopped.10 At most, owners of the project are required to “mitigate” impacts like putting in a fish culvert, a sort of road for fish, arbitrarily replacing habitat elsewhere, or leaving a lone tree with a bird’s nest intact.

The long and growing list of at-risk species shows these measures are not successful in preventing wildlife decline. What’s needed is an effective and comprehensive law that protects species at risk and native ecosystems.

Conditions to protect biodiversity:

- Identify species at risk

- Make it illegal to kill them

- Legally protect their habitat and help them recover

- Ensure healthy wildlife populations stay that way by protecting ecosystems

- Hold governments and industry accountable to laws

- Enshrine United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

In addition, any new law must be co-developed with Indigenous Peoples and uphold UNDRIP, so sovereignty over traditional lands is built in from its inception. There must be funding and support for Indigenous leadership to protect wildlife.

Lastly, and often forgotten, is the need for a plan to keep species of the endangered list by maintaining healthy ecosystems. Wildlife that aren’t currently at risk need ecosystem protection from industrial projects to avoid becoming at risk. What good is a law if it doesn’t protect wildlife until they’re in real trouble?

If we had laws that achieved this, there would be a layer of protection before an industrial project is proposed. Corporations would be inclined to avoid harming habitat and wildlife before developing plans and submitting applications. Projects that would severely damage wildlife simply wouldn’t be allowed, and our local economies would inherently become more sustainable.

Currently, there are six provinces and territories without standalone species-at-risk laws in Canada: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, P.E.I., Nunavut and the Yukon.

THE GRADES ARE IN — WE’RE FAILING BIODIVERSITY

The report cards below grade four jurisdictions throughout Canada on how well they’re protecting biodiversity, including species at risk and ecosystems, based on six conditions.

DESTRUCTION IS DRIVEN BY THE SYSTEM, NOT HUMAN NATURE

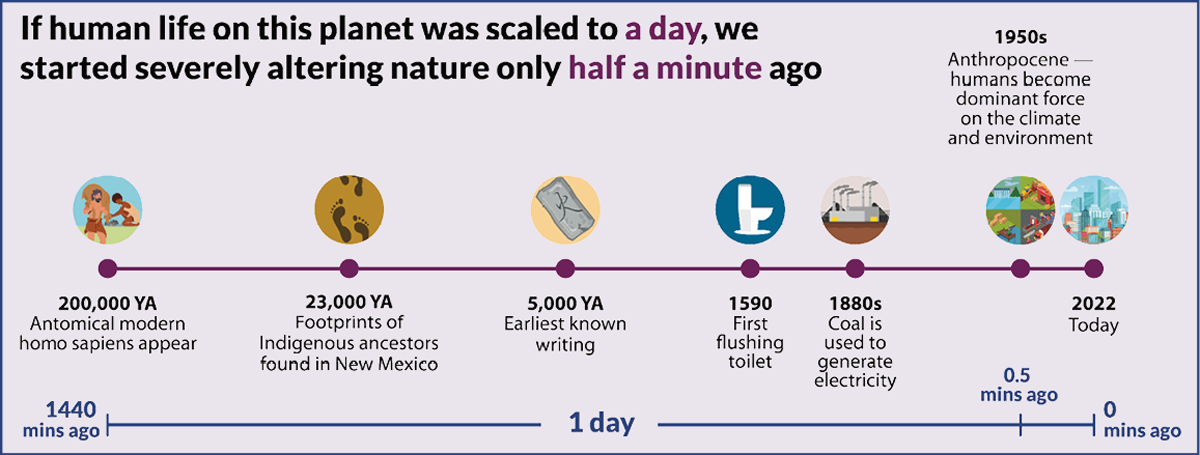

The mid-1900s is often referred to as the beginning of the Anthropocene. Human activity has overtaken geological forces as the dominant influence over the climate and environment in this period. The Anthropocene coincides neatly with industrial-scale mining, logging and fossil fuel extraction in Canada, and dramatic wildlife declines.

The extinction rates we’re causing today are driven by our relatively new system that prioritizes corporate pro ts above all else and demands ever-increasing extraction. The impossible pursuit of infinite growth on a nite planet remains one of the most harmful ideas in history. But there have always been better ways of living on these lands. These ways restore rather than degrade ecosystems and cherish instead of exploiting wildlife.

Beverly swamp, ON (WC Files)

Indigenous-managed lands harbour more biodiversity than any other areas in the world, including protected areas.30Indigenous worldviews and governance systems show us that human presence on the landscape is not fundamentally harmful. The biodiversity crisis is not a problem intrinsic to human nature — it’s a problem rooted in the systems of colonialism and capitalism in which power is entrenched. It’s essential to name these things to understand it doesn’t have to be this way. Change is possible.

We have a chance to change course and save biodiversity with strong laws. With these laws, we can also create jobs in species and ecosystem recovery and shift towards justice for Indigenous Peoples who’ve always lived here. This is ambitious, but all living creatures deserve nothing less.

It’s not too late to reforge our connection to the land and wildlife. The simple act of spending time in natural spaces starts this process. Next, we can look for ways to align our daily actions with the planet’s needs and get involved in efforts to demand politicians do the same with our laws.

Take action!